Deception in Translation: How an Urdu rendering conceals Qur’anic rebuke

It is a foundational principle of Islamic scholarship that a narration must be assessed not only through its chain of transmission (isnād) and textual soundness (matn), but also through the integrity of its transmission in translation. When translation alters meaning, particularly where the text carries moral or theological weight—it ceases to be translation and becomes interpretation.

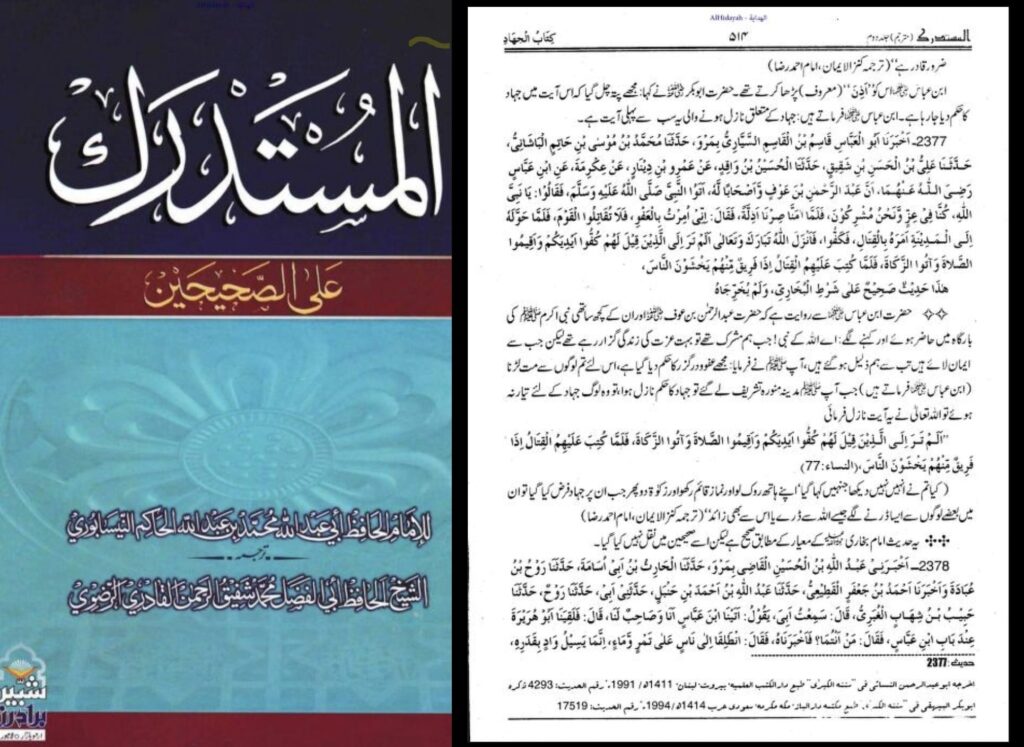

This article examines a clear case of semantic distortion in an Urdu rendering of a narration recorded by al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī (d. 405 AH) in Al-Mustadrak ʿalā al-Ṣaḥīḥayn, a narration that explicitly links the conduct of certain Companions to a Qur’anic rebuke.