Historical and theological problem of the ʿAshura Fast

Among Sunni and Shia traditions alike, the fast of ʿĀshūrāʾ on the 10th of Muharram holds a significant place. However, closer scrutiny of the narrations and historical claims surrounding this fast reveals inconsistencies and raises critical questions about its origin and authenticity.

Narration 1

We read in Sahih Muslim 1130c

وَحَدَّثَنِي ابْنُ أَبِي عُمَرَ، حَدَّثَنَا سُفْيَانُ، عَنْ أَيُّوبَ، عَنْ عَبْدِ اللَّهِ بْنِ سَعِيدِ بْنِ جُبَيْرٍ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنِ ابْنِ عَبَّاسٍ، – رضى الله عنهما – أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم قَدِمَ الْمَدِينَةَ فَوَجَدَ الْيَهُودَ صِيَامًا يَوْمَ عَاشُورَاءَ فَقَالَ لَهُمْ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” مَا هَذَا الْيَوْمُ الَّذِي تَصُومُونَهُ ” . فَقَالُوا هَذَا يَوْمٌ عَظِيمٌ أَنْجَى اللَّهُ فِيهِ مُوسَى وَقَوْمَهُ وَغَرَّقَ فِرْعَوْنَ وَقَوْمَهُ فَصَامَهُ مُوسَى شُكْرًا فَنَحْنُ نَصُومُهُ . فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” فَنَحْنُ أَحَقُّ وَأَوْلَى بِمُوسَى مِنْكُمْ ” . فَصَامَهُ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم وَأَمَرَ بِصِيَامِهِ .

Ibn’Abbas (Allah be pleased with both of them) reported that the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) arrived in Medina and found the Jews observing fast on the day of ‘Ashura. The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said to them: What is the (significance) of this day that you observe fast on it? They said: It is the day of great (significance) when Allah delivered Moses and his people, and drowned the Pharaoh and his people, and Moses observed fast out of gratitude and we also observe it. Upon this the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said: We have more right, and we have a closer connection with Moses than you have; so Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) observed fast (on the day of ‘Ashura), and gave orders that it should be observed.

Sahih Muslim 1130c

https://sunnah.com/muslim:1130c

Narration 2

We read in Sahih Muslim 1134a

وَحَدَّثَنَا الْحَسَنُ بْنُ عَلِيٍّ الْحُلْوَانِيُّ، حَدَّثَنَا ابْنُ أَبِي مَرْيَمَ، حَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى بْنُ أَيُّوبَ، حَدَّثَنِي إِسْمَاعِيلُ بْنُ أُمَيَّةَ، أَنَّهُ سَمِعَ أَبَا غَطَفَانَ بْنَ طَرِيفٍ الْمُرِّيَّ، يَقُولُ سَمِعْتُ عَبْدَ اللَّهِ، بْنَ عَبَّاسٍ – رضى الله عنهما – يَقُولُ حِينَ صَامَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَوْمَ عَاشُورَاءَ وَأَمَرَ بِصِيَامِهِ قَالُوا يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ إِنَّهُ يَوْمٌ تُعَظِّمُهُ الْيَهُودُ وَالنَّصَارَى . فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم “ فَإِذَا كَانَ الْعَامُ الْمُقْبِلُ – إِنْ شَاءَ اللَّهُ – صُمْنَا الْيَوْمَ التَّاسِعَ ” . قَالَ فَلَمْ يَأْتِ الْعَامُ الْمُقْبِلُ حَتَّى تُوُفِّيَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم.

Ibn ‘Abbas reported that when the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) fasted on the day of ‘Ashura and commanded that it should he observed as a fast, they (his Companions) said to him: Messenger of Allah, it is a day which the Jews and Christians hold in high esteem. Thereupon the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said: When the next year comes, God willing, we would observe fast on the 9th But the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) died before the advent of the next year.

Sahih Muslim 1134a

https://sunnah.com/muslim:1134a

Both hadith has often been cited to establish the fast’s legitimacy and link it to pre-Islamic religious traditions. Yet, they reveal several critical pro

The hadith in Sahih Muslim 1130c claims that upon arriving in Medina, the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) found the Jews fasting on the day of ‘Ashura (10th of Muharram), and when he inquired about it, he was told that it commemorated the day when Allah saved Musa (Moses) and drowned Pharaoh. The Prophet is then reported to have said, “We have a greater right to Musa than they do,” and he joined in the fast (Sahih Muslim, 1130c).

These hadith is frequently cited in Sunni literature to justify fasting on the 10th of Muharram. However, a careful study reveals that the narration is deeply flawed when examined through the lenses of history, the Jewish calendar, and the political motivations of later narrators.

Observation One: The narrations contradict one another

This is evident if one compares the two.

Narration 1 (Sahih Muslim 1134)

• The Prophet (s) observed and instructed the fast of ʿĀshūrāʾ, but people said:

“O Messenger of Allah! This is a day that the Jews and Christians venerate.”

• The Prophet (s) replied:

“If I live until next year, I will also fast on the ninth of Muharram.”

• However, the Prophet (s) died before the next year arrived, so the ninth of Muharram fast was never established.

Narration 2 (Sahih Muslim 1130c)

• The Prophet (s) arrived in Medina and found the Jews fasting on ʿĀshūrāʾ.

• He asked them why, and they said it commemorated Allah saving Moses and drowning Pharaoh.

• The Prophet (s) said:

“We have more right to Moses than you,”

• Then the Prophet (s) fasted on ʿĀshūrāʾ himself and ordered his followers to fast it.

The Contradiction

Aspect |

Narration 1 |

Narration 2 |

Timing of the fast |

The fast was instituted late in the Prophet’s life, near the time of his death. |

The fast was observed immediately upon the Prophet’s arrival in Medina (early Hijrah). |

Fast established or not? |

The Prophet (s) planned to add the 9th fast next year but died before doing so, implying the fast was a new command late in his life. |

The Prophet (s) immediately fasted ʿĀshūrāʾ after learning about the Jewish fast, making it an early practice. |

Relation to Jewish practice |

The fast was reluctantly accepted despite its similarity to Jewish and Christian veneration; suggestion to add a new fast shows hesitance. |

The Prophet (s) explicitly endorsed and adopted the Jewish fast of ʿĀshūrāʾ, affirming its legitimacy early on. |

Chronological implication |

Implies the fast was introduced very late in the Prophet’s life, possibly near his death. |

Implies the fast was instituted immediately after Hijrah, years before the Prophet’s passing. |

• These two narrations cannot both be correct in their timeline:

– If the Prophet (s) fasted ʿĀshūrāʾ immediately after arriving in Medina (early Hijrah), he obviously could not have planned to add the 9th the following year near his death, several years later.

– Conversely, if the fast was a new command very late in the Prophet’s life (Narration 1), it contradicts the idea that he fasted it immediately upon arrival in Medina (Narration 2).

Observation Two: 24 September 622 = 12 Tishrei 4383 in the Jewish Calendar

It is well established that the Prophet (ﷺ) arrived in Medina on Monday, 12 Rabi‘ al-Awwal, corresponding to 24 September 622 CE

https://alimaanonline.com/the-migration-hijrah-of-the-prophet-muhammad-saw

This date provides a firm chronological reference to examine the historical plausibility of the hadith.

Neither Jews nor Christians have any historical tradition of fasting on the 10th of Muharram or any equivalent day in their calendars.

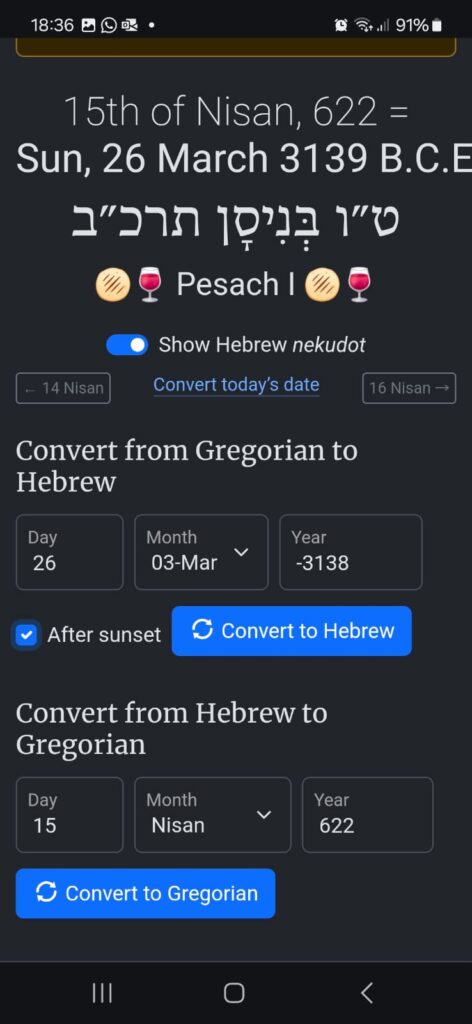

According to the Jewish calendar, 24 September 622 CE corresponds to 12 Tishrei 4383 (Hebcal Jewish Calendar Converter).

(put a calendar here)

This places the Prophet’s arrival just two days after Yom Kippur (10 Tishrei), the Jewish Day of Atonement. Importantly, Yom Kippur has nothing to do with the story of the Exodus, which Jews observe as Passover

Observation Three: Passover in 622 CE Occurred Six Months Earlier

The Hebrew Bible identifies the month of the Exodus as Abib (אָבִיב), which was the name of the first month in the ancient Hebrew calendar. In Exodus 13:4, Moses tells the Israelites, “This day you are going out, in the month of Abib.” Likewise, Deuteronomy 16:1 commands: “Observe the month of Abib and keep the Passover to the LORD your God, for in the month of Abib the LORD your God brought you out of Egypt by night.” These verses make it clear that the Exodus occurred in the month of Abib.

Following the Babylonian exile, the name Abib was replaced by Nisan (נִיסָן), and the post-exilic texts such as Nehemiah 2:1 confirm this renaming while still maintaining its position as the first month. Therefore, Abib and Nisan are the same month—the month of the Passover.

According to Exodus 12:6, the Israelites were commanded to slaughter the Passover lamb on the 14th of this month and eat it that evening, which marked the beginning of the 15th of Abib/Nisan, since Jewish days begin at sunset.

Leviticus 23:5–6 confirms:

“In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at twilight, is the Lord’s Passover. And on the fifteenth day of the same month is the Feast of Unleavened Bread to the Lord.”

This firmly places the commemoration of the Exodus on 15 Nisan.

As per the Jewish calendar, the Passover (Hebrew: Pesach / פֶּסַח) begins on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan. In 622 CE, the year of the Prophet Muhammad’s migration to Medina, 15 Nisan fell on 26 March—a spring date.

This was almost six months before the Prophet’s arrival in Medina, which occurred in late September. There is no record—nor any calendrical possibility—of Jews fasting in September for an event that, within Judaism, is strictly tied to spring.

The hadith reports suggesting that the Jews were fasting on ʿĀshūrāʾ (10th Muharram) in imitation of Moses’ gratitude for the Exodus are therefore historically implausible.

Observation Four: The Exodus Is Not Commemorated with a Fast

Passover, the Jewish festival marking the Exodus, is celebrated with festive meals (Seder), unleavened bread, and praise—not fasting. In fact, fasting is prohibited on Passover, there is in fact an obligation for all Jews to eat. This is evidenced by Chametz U’Matzah – Chapter Seven verse 7 that reads:

Therefore, when a person feasts on this night, he must eat and drink while he is reclining as is the practice of free men. Each and every one, both men and women, must drink four cups of wine on this night. This number should not be reduced. Even a poor person who is sustained by charity should not have fewer than four cups.

https://alimaanonline.com/the-migration-hijrah-of-the-prophet-muhammad-saw

Thus, the hadith’s assertion that Jews were fasting in remembrance of Musa’s deliverance from Pharaoh contradicts Jewish religious practice.

Observation Five: Confusion Between Ashura and Yom Kippur Fails

Some have argued that the Jews the Prophet encountered were observing Yom Kippur, and that the narrator mistakenly linked this to the Exodus. But this suggestion fails for two reasons:

-

Yom Kippur is a day of repentance and atonement, not a celebration of salvation from Pharaoh.

-

The hadith explicitly links the fast to Musa’s Exodus, not to repentance or atonement.

This indicates a deeper error or deliberate fabrication in the transmission of the hadith.

Observation Six: The Hadith Was Fabricated to Reframe Ashura and Obscure Karbala

The most compelling explanation for the hadith promoting fasting and celebratory acts on ‘Ashura is political. It was likely fabricated after the martyrdom of Imam Husayn (peace be upon him) in order to redefine the significance of that day. By constructing a positive, spiritual narrative centered on a prophetic fast, the narrators deliberately shifted attention away from the Umayyad massacre of the Prophet’s family and toward an invented act of piety.

Historical records indicate that the Umayyads viewed the killing of Imam Husayn as revenge for the death of ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affan, the third caliph. This intent is evident in multiple reports:

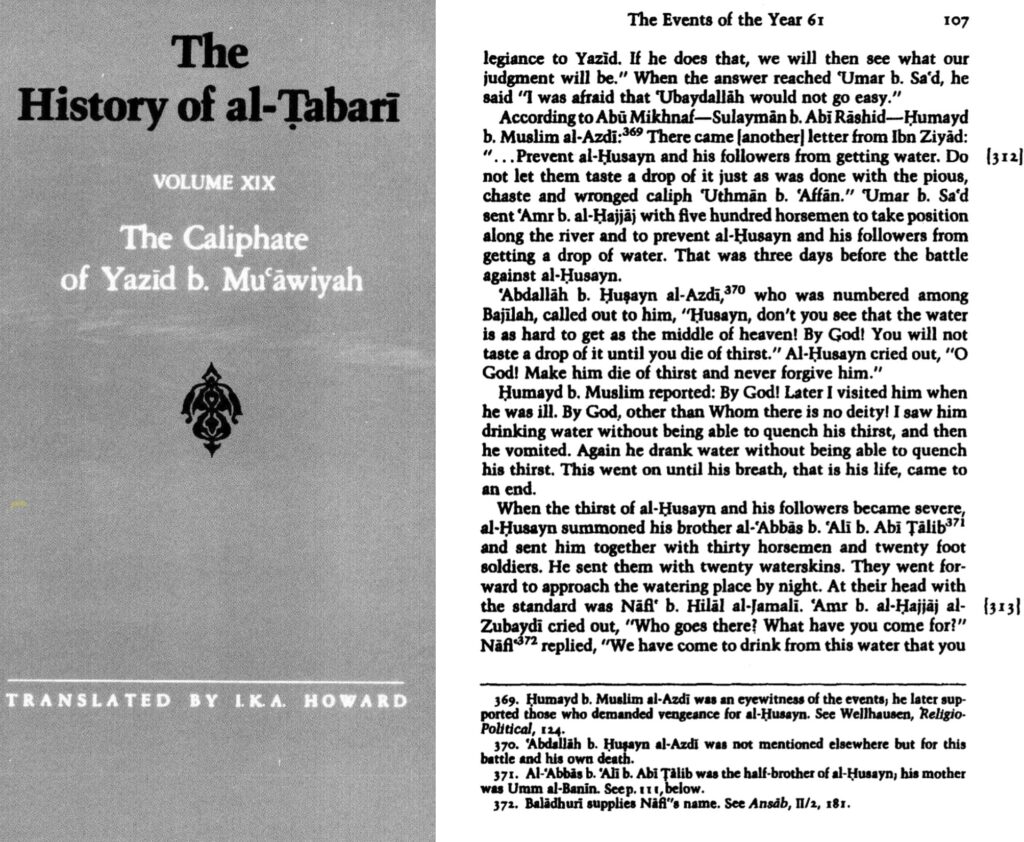

ʿUbaydullāh ibn Ziyād wrote to Umar ibn Saʿd:

“…Prevent al-Husayn and his followers from getting water. Do not let them taste a drop of it just as was done with the pious, chaste and wronged caliph ‘Uthman b. ‘Affan.” “Umar b. Sa’d sent ‘Amr b. Al-Hajjāj with five hundred horsemen to take position along the river and to prevent al-Husayn and his followers from getting a drop of water”.

(History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume 19, page 107)

Following the murder of Imam Husayn, Ibn Ziyād wrote to the Governor of the Two holy sites, ʿAmr ibn Saʿīd al-Umawī, who publicly announced the killing. When the women of Banū Hāshim wept aloud, ʿAmr ibn Saʿīd remarked:

“This is in revenge for the crying of the wives of ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān.”

Those who celebrate on the day of ‘Ashura, claiming that Islam was victorious on that day, are in fact following the tradition of those who rejoiced at the slaughter of Husayn. For them, ‘Ashura became an occasion of inherited joy—because they viewed the death of the Prophet’s grandson as vengeance for Uthmān and for those killed at Badr and Uhud.

This context explains the necessity of fabricating hadiths that portrayed ‘Ashura as a day of joy and religious merit. These narrations offered spiritual cover for this inherited glee. They reframed a day of mourning into a day of fasting and pious acts—thus aligning the Umayyad narrative with supposed prophetic tradition.

Indeed, after the martyrdom of Sayyid al-Shuhadā’ (peace be upon him), the Nasibis fabricated numerous hadiths about the virtues of ‘Ashura and falsely attributed them to the Noble Prophet ﷺ. Even Sunni scholars have admitted that the narrations praising ‘Ashura are fabrications.

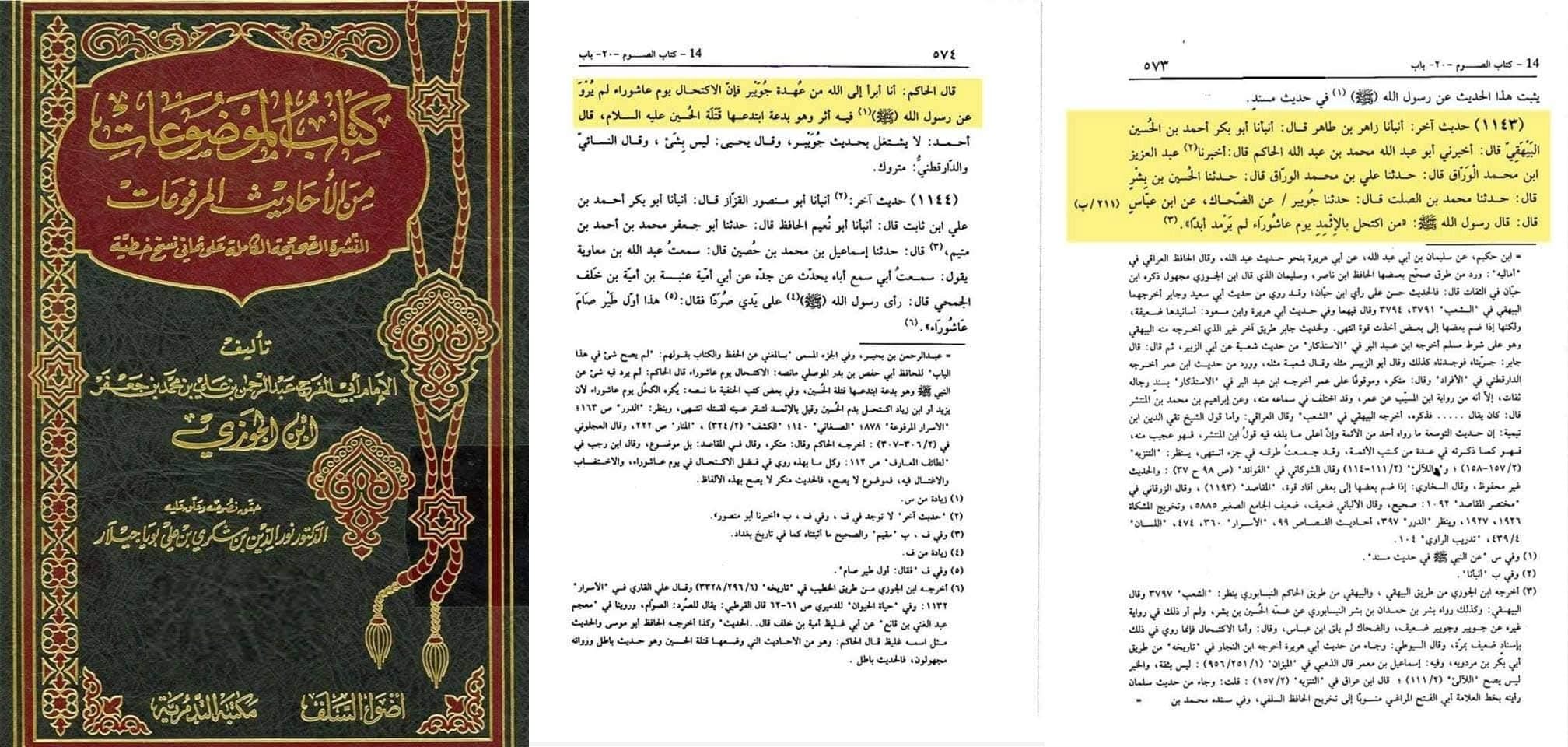

Imam Ibn al-Jawzī narrates:

Zāhir ibn Ṭāhir reported from Abū Bakr Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥusayn al-Bayhaqī, who narrated from Muḥammad ibn ‘Abdullāh al-Ḥākim, from ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad al-Warrāq, from ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad al-Warrāq, from al-Ḥusayn ibn Biṣr, from Muḥammad ibn al-Ṣalāt, from Juwaybir, from al-Ḍaḥḥāk, from Ibn ‘Abbās:

“The Prophet (ﷺ) said: Whoever applies kohl to his eyelids on the day of ‘Ashura will never suffer from sore eyes.”

Imām al-Ḥākim al-Nīshābūrī responded:

“I absolve myself before Allah from Juwaybir. The narration about applying antimony (kohl) to the eyes on ‘Ashura was not reported from the Prophet (ﷺ); rather, it was a bid‘ah (innovation) introduced by the murderers of Ḥusayn (peace be upon him).”

Footnote by Dr. Nūr al-Dīn ibn Shākir:

“The application of kohl to the eyelids is makrūh (discouraged) on the day of ‘Ashura, as either Yazīd or Ibn Ziyād smeared the blood of Ḥusayn (peace be upon him) on his eyes. Some said it was done mockingly—as if to say, ‘his murder is complete.’”

(Source: Kitāb al-Mawḍū‘āt min al-Aḥādīth al-Marfu‘āt, Vol. 1, pp. 573–574)

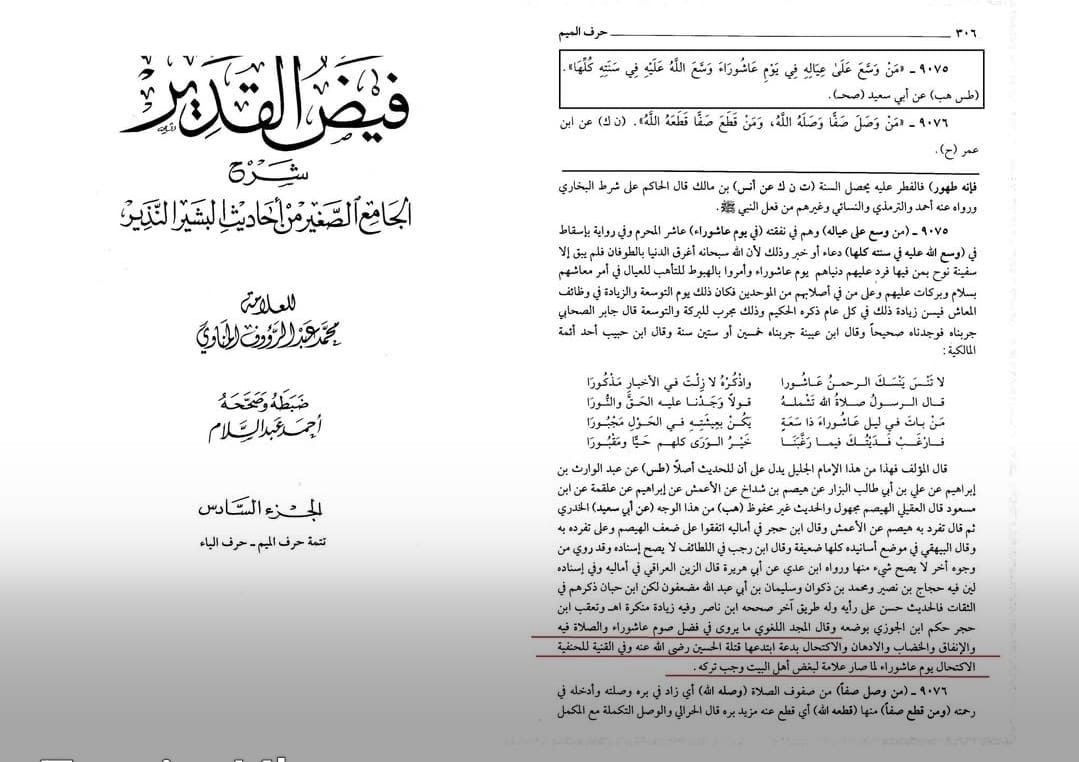

Similarly, Imam Tājj al-‘Ārifīn al-Manāwī recorded the following statement:

ما يُروى في فضل صوم يوم عاشوراء والصلاة فيه والإنفاق والخِضاب والأدهان والاكتحال بدعة ابتدعها قتلة الحسين (رضي الله عنه)، وعلامة لبغض أهل البيت، وجب تركه.

“Whatever has been narrated about the virtues of fasting on ‘Ashura, praying on that day, spending in charity, dyeing (with henna), applying oil to the hair, or using kohl—all of it is a bid‘ah (innovation) initiated by the killers of Ḥusayn (may Allah be pleased with him), and a sign of hatred toward the Ahl al-Bayt. It is obligatory to abandon such practices.”

(Source: Fayḍ al-Qadīr Sharḥ al-Jāmi‘ al-Ṣaghīr, Volume 6, p. 306)

Conclusion:-

The claim that Jews and Christians traditionally fasted on ʿĀshūrāʾ (the 10th of Muharram) finds no solid foundation in their own religious texts or historical practices. Moreover, the Qur’anic and biblical chronologies do not support the commonly cited link between this date and the events of the Exodus or Pharaoh’s drowning.

The hadith narrations that purportedly establish the fast’s origin present notable contradictions and chronological inconsistencies, casting serious doubt on their authenticity and reliability.

Taken together, these issues call into question the legitimacy of the ʿĀshūrāʾ fast as a direct and unequivocal religious injunction from the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ). Instead, the evidence suggests it may have been shaped by cultural influences or political agendas that emerged after the Hijrah.

Notably, the relevant hadith recorded in Sahih Muslim exhibit three critical flaws:

-

They are chronologically implausible,

-

Theologically problematic,

-

Politically expedient.