First attempt – The hadith is an illogical lie

Ibn Taymiyya, in his attempt to refute the hadith «عليٌّ وليُّ كلِّ مؤمنٍ بعدي», begins by rejecting it outright as a fabrication. In Minhāj al-Sunnah fī al-Radd ʿalā al-Shīʿah, volume 7, page 391, he states:

«وكذلك قوله هو وليّ كلّ مؤمن بعدي كذب على رسول الله صلى الله عليه وآله وسلم، بل هو في حياته وبعد مماته وليّ كلّ مؤمن، وكلّ مؤمن وليّه في المحيا والممات، فالولاية التي هي ضدّ العداوة لا تُخصّ بزمان.»

“Similarly, the statement ‘He is the walī of every believer after me’ is a lie against the Messenger of Allah. Rather, during his life and after his death, he is the walī of every believer, and every believer is his walī in life and in death. Walāyah, which is the opposite of ʿadāwah, is not restricted by time.”

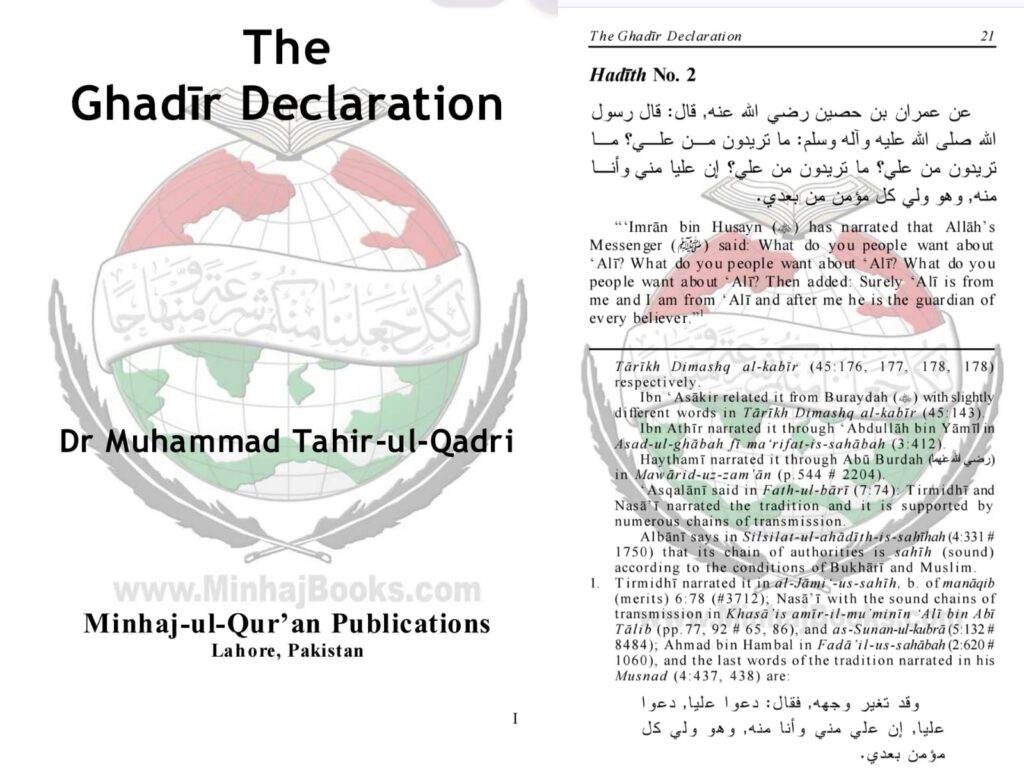

Reply One – Many Sunni scholars have authenticated this narration

This reckless claim is refuted by the very Sunni hadith authorities whom Ibn Taymiyya purported to defend. We have cited 31 Sunni scholars that authenticated this hadith. By way of example, Musnad Aḥmad records the narration, and Aḥmad Muḥammad Shākir affirms:

“The chain of this hadith is Ṣaḥīḥ. Yazīd al-Rashq is Ibn Abī Yazīd, trustworthy according to all scholars as mentioned before. This hadith is also narrated by al-Tirmidhī in Faḍāʾil ʿAlī and graded Ḥasan Gharīb. Al-Ḥākim declared it Ṣaḥīḥ on the conditions of Muslim, and al-Ḍhahabī confirmed it”.

(Musnad Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, vol. 15, pp. 78–79)

Likewise, al-Zarqānī in Sharḥ al-Mawāhib al-Ladunniyya (4:542) upholds its authenticity.

Reply Two – Ibn Taymiyya’s Unreliable Hadith Methodology: A documented litany of errors

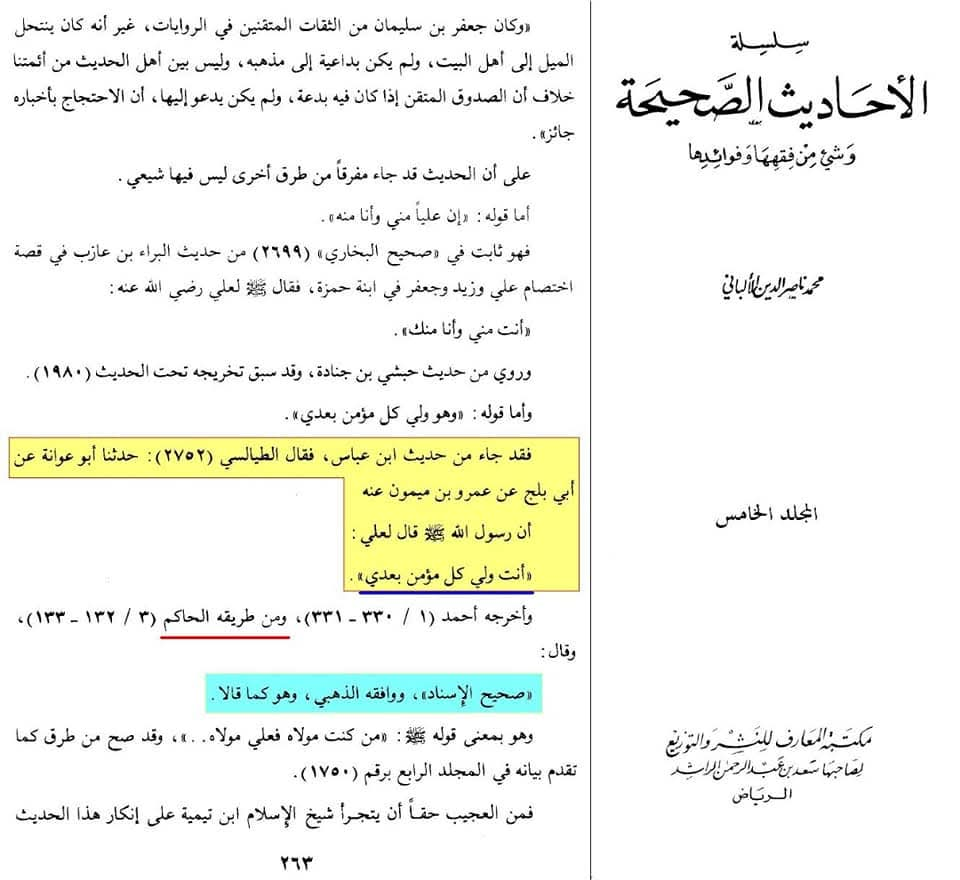

Across numerous works, al-Albani repeatedly refuted Ibn Taymiyya’s hadith judgments, showing that he authenticated very weak or even fabricated narrations, misquoted earlier sources, and committed major errors in grading. He criticised him for assertively attributing extremely weak hadith to the Prophet ﷺ (Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Da‘ifa, no. 110; vol. 12, p. 470; vol. 10, p. 155), for relying on narrators unanimously deemed fabricators (Iman li-Ibn Taymiyya, p. 27), for misreporting al-Tirmidhi as saying “hasan” when he only said “gharib,” and for misusing principles by claiming that “the fundamentals of the Sunnah” support a baseless narration (Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Da‘ifa, vol. 14, p. 1239). Al-Albani also showed that Ibn Taymiyya confused marfu‘ and mawquf forms (Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Da‘ifa, vol. 13, p. 550), added wording to a hadith on reciting the basmala aloud that has no basis in al-Tabarani’s al-Kabir or al-Awsat (al-Mu‘jam al-Awsat, vol. 5, p. 89, no. 4756), and mistakenly treated a hadith on the virtue of Sham as marfu‘ (Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Da‘ifa, vol. 1, p. 69). Most strikingly, regarding the hadith “Ali is your wali after me,” al-Albani—after verifying its chains—declared: It is truly astonishing that Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyya denied and rejected this hadith in “Minhaj al-Sunnah” (Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Sahiha, vol. 5, p. 263). These ten examples demonstrate a pattern of recurrent and serious hadith errors, enough that—as al-Albani implies—a full volume could be written on them. It is therefore clear that Ibn Taymiyya cannot be relied upon in this field: he authenticates weak or fabricated narrations, weakens authentic ones due to misunderstanding, and his rejection of this hadith carries no weight beyond reflecting his pro-Nasibi bias. When it came to his rejection of this hadith al-polemical judgment shaped by his broader project against Shi‘i arguments, in Silsilat al-Aḥādīth al-Ṣaḥīḥa (5:263–264), rebuked him:

فمن العجيب حقا أن يتجرأ شيخ الإسلام ابن تيمية على إنكار هذا الحديث وتكذيبه في “منهاج السنة”

“It is truly astonishing that Ibn Taymiyya dared to deny this hadith and dismiss it as a fabrication in Minhāj al-Sunnah.”

Thus Ibn Taymiyya’s rejection was not grounded in hadith criticism but in political prejudice—a refusal to accept any text that would imply succession for ʿAlī (as). The very methodology he used to defend Sunni orthodoxy is here exposed as selective and self-contradictory.

Reply Three – The Absurdity of Ibn Taymiyya’s Claim That Wilāyah Has No Temporal Limits

Whilst insisting the hadith is illogical, his admission is revealing. In affirming that walāyah persists after death and stands as the opposite of ʿadāwah, Ibn Taymiyya effectively confirms that walāyah is a binding relationship, not mere friendship. In this hadith, the Prophet uses wilāyah in a legal-operational sense (‘I am his walī’ in Bukhari 6745), not merely as an emotion. So even if walāyah can sometimes mean love, the Prophetic usage here is already defined as authority. Simple maḥabbah does not continue after death, nor is it defined in the uṣūl as the opposite of ʿadāwah. But authority, allegiance, and binding loyalty are. Thus, his own explanation undercuts his claim that walāyah in the hadith has no authoritative dimension.

Having first dismissed the hadith as “lies,” he then shifts to a hypothetical argument, claiming that even if it were authentic, it would not indicate imārah. He opines:

«وإن أراد الإمارة كان ينبغي أن يقول: والٍ على كلّ مؤمن.»

“And if he intended imārah (authority), he should have said: walin ʿalā kulli muʾmin.”

Here Ibn Taymiyya begins dictating what the Prophet should have said. Instead of accepting the Prophet’s actual wording — «من كنت مولاه فهذا عليٌّ مولاه» — he suggests that the Prophet ﷺ failed to use the “correct” expression. This is not interpretation of prophetic speech; it is an attempt to correct it.

The inconsistency becomes more striking when his usage in other works is examined. If Ibn Taymiyya truly believed that the word walī cannot convey authority without the form “walin ʿalā,” then why does he repeatedly employ walī alone to denote rulers, governors, and political authority? In al-Khilāfah wa al-Mulk, page 15, and again on pages 17–18, he uses walī in precisely this authoritative sense. Sometimes he insists on walin ʿalā, at other times walī by itself, and often both interchangeably. The standard shifts according to polemical needs, not linguistic principles.

His argument thereby collapses from within. Either Ibn Taymiyya deliberately denied meanings he accepted elsewhere simply to undermine a hadith affirming the walāyah of Amīr al-Muʾminīn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, or he failed to maintain a coherent linguistic method. In both cases, the hadith remains unshaken, transmitted in multiple chains and supported by the Prophet’s own wording:

«من كنت مولاه فهذا عليٌّ مولاه»

Second Attempt – Only friendship and affection can be gauged from this hadith not political succession

The implications of the Hadith of Wilāyah are so far-reaching that Sunni scholarship has often felt compelled to soften or redirect its meaning in order to preserve the doctrinal claim that the Prophet ﷺ neither appointed a successor nor formalized a mechanism for succession. Within this framework, the events of Saqīfa are portrayed as an emergency response to an alleged leadership vacuum, in which Abū Bakr merely stepped forward to fill an unforeseen void. It is against this theological backdrop that Sunni translations of the Prophet’s statement—“ʿAlī is from me, and I am from him, and he is the walī of every believer after me”—must be understood.

As has already been established, this hadith contains a crucial temporal qualifier: “after me” (بعدي). This phrase is decisive. It restricts the function of wilāyah to a period following the Prophet’s death, thereby necessitating a meaning that is role-based, functional, and operative in his absence. Any interpretation of walī that denotes a relationship already fully established during the Prophet’s lifetime is rendered immediately incoherent by this clause.

Nevertheless, among segments of South Asian Sunni scholarship, the term walī is frequently minimized to denote personal affection or informal assistance. In their respective Urdu translations of Khaṣāʾiṣ ʿAlī by Imām al-Nasāʾī, for example, Navīd Ḥamīd Rabbānī translates walī as dost (friend) (p. 155), while Sāʾim Chishtī renders it as madadgār (helper/friend) (p. 94). These translations reflect not a linguistic necessity, but a theological discomfort with the implications of the hadith.

This reading, however, collapses under the weight of the Prophet’s own explicit statements concerning Imam Ali (as). In Sahih Muslim, the following hadith is recorded with an unambiguous chain:

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ، حَدَّثَنَا وَكِيعٌ، وَأَبُو مُعَاوِيَةَ عَنِ الأَعْمَشِ، ح وَحَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى بْنُ يَحْيَى، – وَاللَّفْظُ لَهُ – أَخْبَرَنَا أَبُو مُعَاوِيَةَ، عَنِ الأَعْمَشِ، عَنْ عَدِيِّ بْنِ ثَابِتٍ، عَنْ زِرٍّ، قَالَ قَالَ عَلِيٌّ وَالَّذِي فَلَقَ الْحَبَّةَ وَبَرَأَ النَّسَمَةَ إِنَّهُ لَعَهْدُ النَّبِيِّ الأُمِّيِّ صلى الله عليه وسلم إِلَىَّ أَنْ لاَ يُحِبَّنِي إِلاَّ مُؤْمِنٌ وَلاَ يُبْغِضَنِي إِلاَّ مُنَافِقٌ .

Zirr reported: ‘Ali observed: By Him Who split up the seed and created something living, the Apostle (may peace and blessings be upon him) gave me a promise that no one but a believer would love me, and none but a hypocrite would nurse grudge against me.

Sahih Muslim 78

https://sunnah.com/muslim:78

Loving Ali (as), therefore, was already an established criterion of īmān, while enmity toward him was a sign of nifāq. Friendship, affection, and loyalty toward Ali (as) were not newly legislated concepts awaiting activation after the Prophet’s death. Additionally, friendship is not a universal legal relationship vested in a single individual over “every believer.” Authority and guardianship, however, are precisely such universal relations.Consequently, to claim that Ali (as) only becomes the “friend” of believers after the Prophet ﷺ implies either that this relationship did not meaningfully exist beforehand or that it lacked religious consequence—both of which directly contradict explicit Prophetic declarations.

The same logical failure applies, even more starkly, to interpreting *wali* as “helper” (*nasir*). To designate Ali (as) as the “helper of every believer after me” raises unavoidable questions that the hadith does not—and need not—spell out, because their answers are already embedded in the concept of *wilayah*. How is a single individual to function as the helper of **every believer**, across regions, disputes, and crises, without possessing recognized authority? What distinguishes this alleged role from the general Qur’anic command that believers help one another? The Qur’an already establishes mutual assistance as a collective obligation, we for example read in Surah at-Tawbah — verse 71

وَالْمُؤْمِنُونَ وَالْمُؤْمِنَاتُ بَعْضُهُمْ أَوْلِيَاءُ بَعْضٍ

“The believing men and believing women are awliyāʾ of one another.”

As such, appointing a specific individual as the helper of all believers would therefore be redundant unless it entailed **institutional authority and binding leadership.

More critically, appointing a universal helper without appointing a leader is theologically and rationally untenable. If the Prophet (s) deemed it necessary to publicly declare who would “help” the Ummah after him, how could he leave the far more consequential matter of **governance, judgment, and unity** unresolved? Such a scenario portrays the Prophet (s) as meticulous in secondary matters yet negligent in the Ummah’s survival—an implication that no Muslim theology can accept. A helper of the entire Ummah would, by necessity, be a **central point of reference**, vested with the authority to intervene, decide, and command. That authority is precisely what *wilayah* denotes.

Accordingly, interpreting walī in this hadith in a reductive manner—as merely “friend” or “helper”—is not a neutral linguistic choice but a deliberate retreat from the hadith’s plain meaning, its contextual indicators, and its unavoidable logical implications. Only wilāyah understood as authority and guardianship coherently accounts for the timing of the declaration, the specific wording employed, the public and formal nature of the proclamation, and the gravity with which the Prophet (s) conveyed it. Any lesser interpretation renders the statement either redundant or conceptually incoherent.

This selective softening of the term becomes particularly conspicuous when walī is applied outside the case of Imam Ali (as).

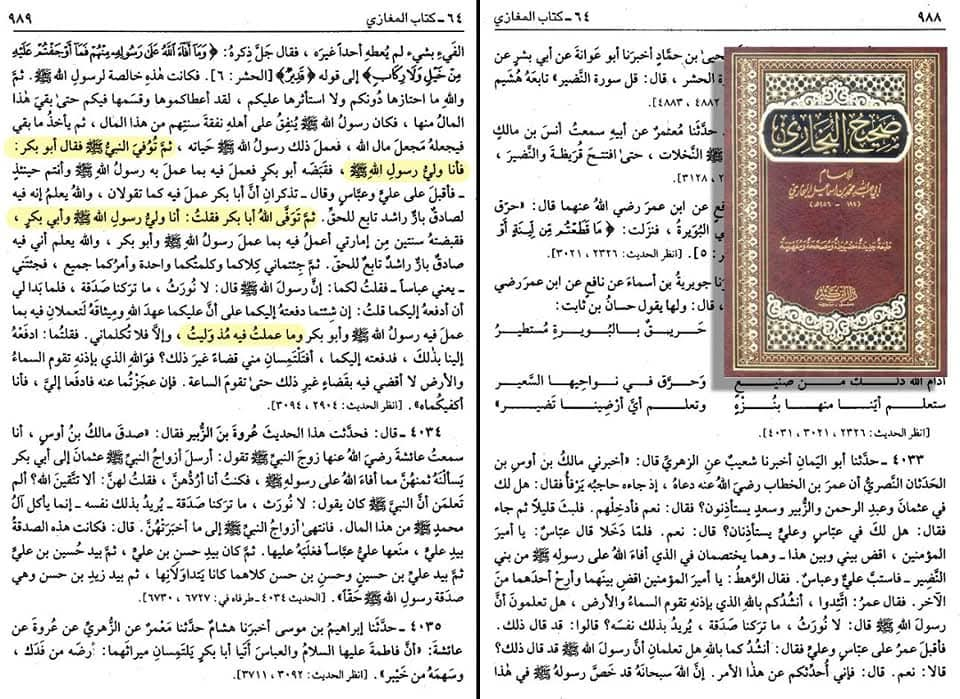

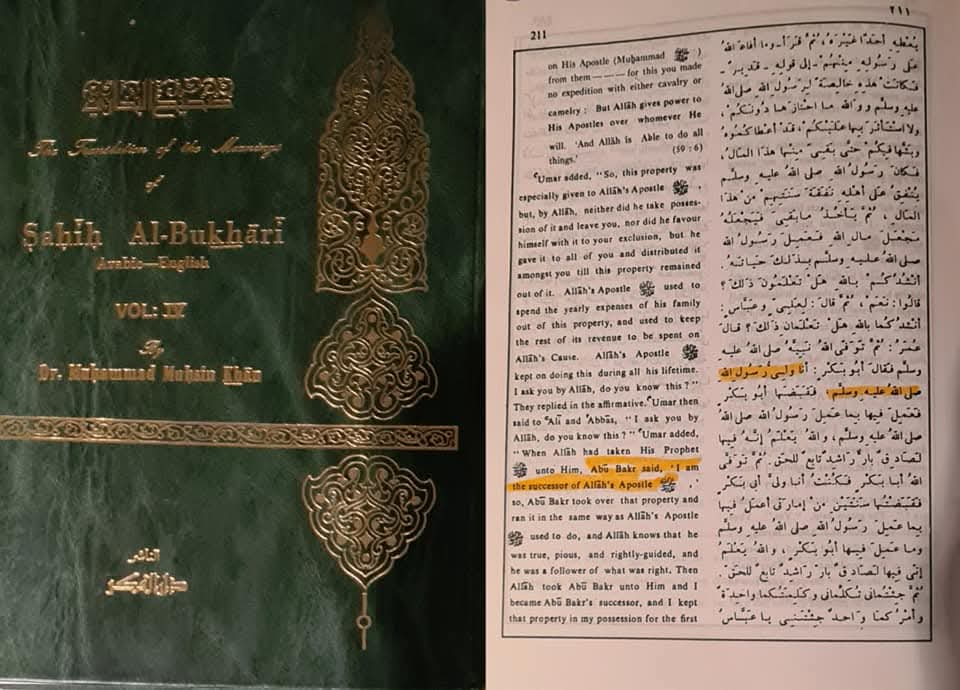

When Abū Bakr assumed authority, he explicitly declared

أَنَا وَلِيُّ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ

“I am the walī of the Messenger of Allah” (Sahih al-Bukhārī, 6728),

Which is universally translated in Sunni sources as “successor” or “authority-holder.” Ibn Kathīr records Abū Bakr’s inaugural address after Saqīfa:

أَمَّا بَعْدُ أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ فَإِنِّي قَدْ وُلِّيتُ عَلَيْكُمْ…

“O people, I have become your walī, but I am not the best among you. If I do well, help me; and if I do wrong, correct me…” (al-Bidāya wa’l-Nihāya, Juz’ 6, p. 301, Dār al-Maʿārif, Beirut).

The chain of narration is ṣaḥīḥ, and even Sunni sources like Twelver.net translate walī as “ruler” here. No alternate meaning is considered plausible. Yet when the Prophet ﷺ assigns walī to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib (as), Sunni scholarship consistently reduces the term to friend or spiritual helper, reflecting doctrinal necessity rather than linguistic evidence.

Linguistic and historical analysis further clarifies the issue. In classical Arabic, Wali (ولي) denotes authority, guardianship, and leadership. The phrase *“Wali min Badhi”* (ولي من بعدي, “my Wali from among you”) clearly conveys leadership and succession. At Ghadir Khumm, the Prophet ﷺ used Maula (مولى), stating: *“For whoever I am his Maula, ʿAlī is his Maula”* (لِمَن كُنْتُ وَلِيَّهُ فَعَلِيٌّ وَلِيُّهُ). Lexical and historical evidence demonstrates a nexus between Wali and Maula, both conveying authority over the believers. The use of Maula in the public Ghadir declaration confirmed and amplified the authority indicated by the earlier Wali designation.

Third Objection: The Hadith of Wilāyah Was Contextual and Insignificant, Addressed Only to a Small Group of Aggrieved Individuals

It is argued that the Hadith of Wilāyah carries no broader doctrinal significance, as it was allegedly uttered by the Prophet ﷺ merely to adjudicate a dispute involving a small number of individuals who harboured grievances against Imam ʿAlī (as). According to this view, the limited audience demonstrates that the statement was situational, momentary, and devoid of any implication of political succession. Had the Prophet ﷺ intended to designate ʿAlī (as) as his heir apparent, it is claimed, he would have done so through a public, ceremonial announcement before a vast assembly of Companions, not in the presence of a handful of complainants. Thus, the hadith is dismissed as a contextual ruling, relevant only to that particular incident and moment in time.

Reply: The Hadith of Wilāyah was a Deliberate Precursor to the Public Declaration at Ghadir

While it is conceded that the Hadith of Wilāyah emerged within a specific context—namely, complaints lodged against Imam ʿAlī (as)—this does not diminish its significance. On the contrary, the choice of language employed by the Prophet ﷺ reveals an intention that transcends the immediate dispute. The Prophet did not merely vindicate ʿAlī (as) against his detractors or issue a situational ruling; rather, he articulated a **principled declaration of Ali’s binding authority over the believers**, explicitly extending **beyond his own lifetime** through the phrase “after me”.

The grievances themselves were so lacking in merit that, as recorded in the sources, even the testimony of four Companions was dismissed. Yet instead of merely resolving the complaint, the Prophet ﷺ escalated the matter into a declaration of *wilāyah*, thereby placing the complainants—and by extension the broader community—on notice. He made it unequivocally clear that Ali’s station was not contingent upon temporary command, personal approval, or popular sentiment. Whether the objectors approved or not, Ali’s wilāyah was binding in the long term. In this sense, the Prophet ﷺ transformed a localized dispute into an authoritative pronouncement about Ali’s enduring role within the Ummah.

This declaration, therefore, functioned as an earlier articulation of a principle later declared publicly. It served to establish the principle of Ali’s *wilāyah* among key individuals before its later, unmistakable public articulation. This also explains why Imam Ali (as), in later disputes over his legitimate rights, did not rely primarily upon the Hadith of Wilāyah, but rather upon the Declaration of Ghadir Khumm, Al-Haythami reports in *Majmaʿ al-Zawāʾid* (Vol. 9, Hadith 14612, pp. 129–130),

قَالَ أَبُو الطُّفَيْلِ: جَمَعَ عَلِيٌّ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ النَّاسَ فِي الرَّحْبَةِ، ثُمَّ قَالَ: أَنْشُدُ اللَّهَ كُلَّ امْرِئٍ مُسْلِمٍ سَمِعَ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ ﷺ يَقُولُ يَوْمَ غَدِيرِ خُمٍّ مَا قَالَ إِلَّا قَامَ. فَقَامَ ثَلَاثُونَ رَجُلًا، فَشَهِدُوا أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ ﷺ أَخَذَ بِيَدِ عَلِيٍّ فَقَالَ: أَلَسْتُ أَوْلَى بِالْمُؤْمِنِينَ مِنْ أَنْفُسِهِمْ؟ قَالُوا: بَلَى يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ. قَالَ: فَمَنْ كُنْتُ مَوْلَاهُ فَهَذَا عَلِيٌّ مَوْلَاهُ، اللَّهُمَّ وَالِ مَنْ وَالَاهُ، وَعَادِ مَنْ عَادَاهُ.

قَالَ أَبُو الطُّفَيْلِ: فَخَرَجْتُ وَفِي نَفْسِي شَيْءٌ، فَلَقِيتُ زَيْدَ بْنَ أَرْقَمَ، فَقُلْتُ لَهُ: إِنِّي سَمِعْتُ عَلِيًّا يَقُولُ كَذَا وَكَذَا. فَقَالَ: فَلَا تُنْكِرْهُ، فَقَدْ سَمِعْتُ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ ﷺ يَقُولُ ذَلِكَ.

Abū al-Ṭufayl said:

“ʿAlī, may Allah be pleased with him, gathered the people at al-Raḥbah and said: *I adjure every Muslim by Allah: whoever heard the Messenger of Allah ﷺ say on the Day of Ghadīr Khumm what he said, let him stand.* So thirty men stood and testified that the Messenger of Allah ﷺ took ʿAlī by the hand and said: *‘Am I not more entitled over the believers than their own selves?’* They replied: *‘Yes, O Messenger of Allah.’* He then said: *‘Whoever I am his mawla, then this ʿAlī is his mawla. O Allah, be the wali of whoever takes him as wali, and be the enemy of whoever shows enmity toward him.’*

Abū al-Ṭufayl said:

“I left while there was something in my heart [i.e., doubt or unease], so I met Zayd ibn Arqam and said to him: *I heard ʿAlī say such-and-such.* He replied: *Do not deny it, for I too heard the Messenger of Allah ﷺ say it.*”

Abū al-Ṭufayl’s reaction to Imam ʿAlī’s (as) public adjuration at al-Raḥbah is itself decisive evidence that what was being invoked was far more than a declaration of friendship. He explicitly states, “I left while there was something in my heart,” a phrase that in hadith literature signifies intellectual disturbance and astonishment, not casual uncertainty. This reaction would be inexplicable if Imam ʿAlī (as) were merely asking witnesses to affirm that the Prophet ﷺ loved him or regarded him as a friend—a fact already established as a criterion of īmān and never disputed. The need Abū al-Ṭufayl felt to seek out Zayd ibn Arqam for independent verification further underscores the gravity of the claim; such corroboration is sought only when a statement carries binding juridical or political implications, not when it concerns personal affection. His unease and subsequent confirmation make sense only if the testimony concerned a declaration of authority that challenged prevailing assumptions, thereby demonstrating that the Ghadīr proclamation was understood by contemporaries as a designation of leadership, not a reaffirmation of friendship.

In sum, the earlier, restricted-audience declaration of wilāyah ensured accurate transmission, accountability, and notice among key Companions, while the later public declaration at Ghadīr Khumm secured mass recognition and communal obligation. Read together, these staged declarations expose the methodological weakness of objections grounded in context, audience size, or timing, and instead confirm a deliberate Prophetic strategy culminating in the explicit designation of Imam ʿAlī (as) as the leader of the Ummah after the Prophet ﷺ.

Fourth Objection – the words min badhi are the concoction of a Shia narrator

Farid, in his article on http://Twelver.net, makes the following assertions regarding the hadith

«علي ولي كل مؤمن بعدي»:

”As for Ja’afar bin Sulaiman, he is a Shi’ee according to Ibn Sa’ad, Al-Muqadami, Ibn Adi, Ibn Hibban, Al-Azdi, Al-Duri, and Yazeed bin Harun. See Al-Tatheeb.”

”It becomes even more apparent that Al-Ajlah made a mistake when we go back to other narrations of Buraida Al-Aslami, since none of them have the addition that includes the term “after me”.

For example, we find an authentic narration from Sa’eed bin Jubair from Ibn Abbas from Buraida in the Musnad (16/475) without this addition. Abdul Jaleel bin Atiya (22/483), Ali bin Suwaiyid bin Manjoof (22/506), and Sa’ad bin Ubaida (22/511) (Sa’ad narration is by Al-A’amash who narrated with ‘an’ana) also narrated it without the addition from Abdullah bin Buraida from his father. All of these can also be found in Musnad Ahmad. With this in mind, it is quite clear that neither Buraida, nor his son, said the word “after me”, since none of the reliable narrators mentioned such a thing when narrating from them.”

Ja’afar bin Sulaiman, being a contemporary of Al-Ajlah, may have heard this narration in this form, and narrated it in the same manner. Unlike what Al-Albani is implying, an innovator may be affected by his innovation, but without it having anything to do with his truthfulness. Ja’afar bin Sulaiman wouldn’t be lying by adding the terms “after me”, but rather, would be narrating the narration according to the meaning that he has understood it in.

It should also be known that there are other chains that support the version without the addition and are of the highest authenticity. This includes the narration of Sa’ad bin Abi Waqqas and Sa’eed bin Wahb, both of which are in Khasa’is Ali (p. 75-76).

The narration is also authentic in Sunan Al-Tirmithi (p. 845) in the narration of Abu Al-Tufail from either Zaid bin Arqam or Abi Sareeha. It too doesn’t contain this addition.

With the above in mind, one can easily be reassured that Buraida, Sa’ad, Zaid bin Arqam/Abi Sareeha, and Sa’eed bin Wahb, through authentic chains, have narrated this without the addition of “after me”, and that these narrations are stronger than the narrations that include the addition.

Reply One – There is no evidence of a Shi’a engineered conspiracy

Sunni hadith methodology does not treat variation between concise and expanded wordings as evidence of fabrication. The principle of ziyādat al-thiqah establishes that an addition transmitted by a reliable narrator is accepted unless it contradicts stronger transmission. Farid’s argument that the wording علي ولي كل مؤمن بعدي is a Shīʿī interpolation collapses entirely once the actual Sunni hadith record is reviewed. His claim depends on two assumptions: that the phrase “after me” was inserted by Shīʿī-leaning transmitters like Jaʿfar b. Sulaymān or al-Ajlah, and that the absence of this phrase in some narrations from Buraida or Saʿd proves it is inauthentic. Both assumptions are incorrect. The wording بعدي is preserved through multiple, independent, fully Sunni and fully authenticated chains that do not rely on Jaʿfar b. Sulaymān or any Shīʿī narrator.

Al-Tayalisi, Musnad Abu Dawud al-

Narrated to us, Abu Dawud narrated to us, Abu ‘Awana narrated to us from Abu Balaj from ‘Amr ibn Maymun from Ibn ‘Abbas, who reported: The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said to ‘Ali: “You are the Wali of every believer after me.”

Grading & Reference: Graded authentic by Al-Albani. See: Al-Albani, Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Sahihah, Vol. 5, p. 223.

In the Shamela digital library, it is listed as Hadith number 2875.

https://shamela.ws/book/1456/3477?utm

Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Musnad, Vol. 4, p. 437

‘Abdullah narrated to us, his father narrated to him, Yahya ibn Hammad narrated to us, Abu ‘Awana narrated to us, Abu Balaj narrated to us, from ‘Amr ibn Maymun, who said: I was sitting with Ibn ‘Abbas when the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said: “You are my Wali in every believer after me.”

Grading & Reference: Graded authentic by Al-Albani, Silsilat al-Ahadith al-Sahihah, Vol. 5, p. 222.

In Musnad Aḥmad (printed version) / Musnad Ibn Ḥanbal: Arabic Dawate Islami’s copy shows: Book 1 / p. 452

https://www.arabicdawateislami.net/bookslibrary/1524/page/452?utm

These two Sunni narrator chains alone, both deemed ṣaḥīḥ by a major Salafī hadith critic, decisively refute any allegation of a sectarian interpolation. The wording “after me” is not dependent on a single narrator, let alone a Shīʿī one; it is preserved through Sunni routes with fully acceptable narrators.

Farid’s second claim—that because some narrations do not include “after me” none of the Sahaba ever said it—is methodologically indefensible. Differences in matn wording between narrations are ubiquitous in Sunni hadith literature and never constitute grounds for dismissing one version as fabricated. Hadith al-Ghadīr, Hadith al-Thaqalayn, and many other well-known reports appear in shorter and longer forms across different companions; no Sunni scholar claims that the fuller versions are fabrications simply because another chain transmits a shorter text. Variance is normal, expected, and especially common when narrations circulate from different companions, in different contexts, or are transmitted by narrators who summarise portions of an event. Farid’s logic would require rejecting hundreds of Sunni hadiths, an impossibility within the methodology of hadith criticism. The mere presence of shorter narrations does not cancel or outweigh the existence of longer, authenticated ones—especially when the longer form is backed by multiple independent Sunni chains judged reliable by Sunni critics.

Moreover, Farid’s discomfort with the wording “after me” (min baʿdī) ignores a crucial point: the Prophet ﷺ frequently and explicitly spoke about what would occur after his death. In the Ṣaḥīḥayn alone, he warned the companions that some would introduce innovations and be turned away from the Ḥawḍ (Bukhārī 7049), and that tribulations would descend upon the Ummah like raindrops (Bukhārī 7060). These warnings are forward-looking guidance, directed specifically at the post-Prophetic era.

The Prophet ﷺ consistently acted as a shepherd (rā‘in) over his flock (ra‘iyya), emphasizing that every shepherd is fully accountable for those under his care (Sahih al-Bukhari 7138; Sahih Muslim 1829a). Leaving the Ummah leaderless would have been like abandoning a flock to wander into danger. Just as a shepherd must appoint a guardian to protect the flock, the Prophet ﷺ explicitly designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib عليه السلام as the walī of every believer “after me”.

The wording min baʿdī is therefore entirely consistent with the Prophet’s established pattern of forward-looking guidance. It is not a fabrication or anomaly; it reflects his role as the ultimate guardian, ensuring that the flock would continue to be guided, protected, and unified after his departure. The designation of leadership “after me” fits perfectly within the broader corpus of Prophetic instruction, linking accountability, responsibility, and authority into a coherent, authentic message.

The idea that the wording “after me” was engineered by a Shīʿī narrator is therefore not only unsupported—it is outright contradicted by the fundamental evidence. We have cited two chains that care free from sectarian bias. The strongest hadith critic on the Salafī side authenticated them. The matn aligns seamlessly with the Prophet’s well-documented habit of discussing posthumous events. Farid’s attempt to dismiss the wording relies not on hadith science but on conjecture driven by theological discomfort. He speculates—without any textual, isnād-based, or historical proof—that Ja‘far bin Sulaymān supposedly added the phrase “after me” because of his Shī‘ī inclination.

However, once this type of conjecture is introduced, Farid’s entire argument collapses under its own weight. If mere possibility is enough to cast suspicion on a wording, then the exact same possibility applies with equal or greater force to the Sunni narrators who transmitted the truncated version.

In other words:

If Farid may claim (without evidence) that the Shīʿī narrator added the phrase due to belief, then it is equally valid to claim—without evidence—that the Sunni narrators removed the phrase due to their belief.

And unlike Farid’s assertion, this latter suspicion actually has historical context behind it: the Sunni polemical efforts to soften the implications of Hadith Ghadīr, Hadith Wilāyah and reinterpret wali and mawla as “friend” are well documented. In such a climate, removal of the phrase “after me” would serve Sunni theology far more directly than its addition would serve a Shīʿī one.

This introduces a methodological problem for Farid:

* He cannot selectively apply conjecture to one narrator while exempting the other.

* He cannot base an objection on speculation that undermines his own version just as easily.

* And once such conjecture is allowed, every variant transmission becomes vulnerable, rendering his argument meaningless.

Therefore:

* his method is invalid,

* his objection is self-destructive, and

* the narration must be evaluated through isnād science alone, not conjectural psychology.

Furthermore, if Farid rejects the ḥadīth of Wilāyah because one transmitter was “Shīʿī,” consistency demands he reject this one, that is typically used to evidence that Muʿawiyah and Yazid will enter Paradise:

حَدَّثَنِي إِسْحَاقُ بْنُ يَزِيدَ الدِّمَشْقِيُّ، حَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى بْنُ حَمْزَةَ، قَالَ حَدَّثَنِي ثَوْرُ بْنُ يَزِيدَ، عَنْ خَالِدِ بْنِ مَعْدَانَ، أَنَّ عُمَيْرَ بْنَ الأَسْوَدِ الْعَنْسِيَّ، حَدَّثَهُ أَنَّهُ، أَتَى عُبَادَةَ بْنَ الصَّامِتِ وَهْوَ نَازِلٌ فِي سَاحِلِ حِمْصَ، وَهْوَ فِي بِنَاءٍ لَهُ وَمَعَهُ أُمُّ حَرَامٍ، قَالَ عُمَيْرٌ فَحَدَّثَتْنَا أُمُّ حَرَامٍ أَنَّهَا سَمِعَتِ النَّبِيَّ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَقُولُ ” أَوَّلُ جَيْشٍ مِنْ أُمَّتِي يَغْزُونَ الْبَحْرَ قَدْ أَوْجَبُوا ”. قَالَتْ أُمُّ حَرَامٍ قُلْتُ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ أَنَا فِيهِمْ. قَالَ ” أَنْتِ فِيهِمْ ”. ثُمَّ قَالَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” أَوَّلُ جَيْشٍ مِنْ أُمَّتِي يَغْزُونَ مَدِينَةَ قَيْصَرَ مَغْفُورٌ لَهُمْ ”. فَقُلْتُ أَنَا فِيهِمْ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ. قَالَ ” لاَ ”.

Ishāq b. Yazīd al-Dimashqī → Yahyā b. Ḥamzah → Thawr b. Yazīd → Khālid b. Maʿdān → ʿUmair b. Al-Aswad al-ʿAnsī told him that he went to ‘Ubada bin As-Samit while he was staying in his house at the sea-shore of Hims with (his wife) Um Haram. ‘Umair said. Um Haram informed us that she heard the Prophet (ﷺ) saying, “Paradise is granted to the first batch of my followers who will undertake a naval expedition.” Um Haram added, I said, ‘O Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ)! Will I be amongst them?’ He replied, ‘You are amongst them.’ The Prophet (ﷺ) then said, ‘The first army amongst’ my followers who will invade Caesar’s City will be forgiven their sins.’ I asked, ‘Will I be one of them, O Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ)?’ He replied in the negative.”

Chapter 93: The fighting against Ar-Rum (the Byzantines), Book 56: Fighting for the Cause of Allah (Jihaad)

https://sunnah.com/bukhari:2924

This isnād is a single, entirely Syrian chain passing through Khalid ibn Maʿdān, a pillar of the Umayyad-era religious establishment. Al-Dhahabī explicitly identifies him as:

«الإِمَامُ، شَيْخُ أَهْلِ الشَّامِ، أَبُو عَبْدِ اللَّهِ الكَلَاعِيُّ الحِمْصِيّ»

“The Imām, the Shaykh of the people of al-Shām, Abū ʿAbd Allāh al-Kalāʿī of Ḥimṣ.”

(Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 5, p. 438)

Al-Dhahabī further notes:

«كَتَبَ الوَلِيدُ إِلَى خَالِدِ بْنِ مَعْدَانَ فِي مَسْأَلَةٍ فَأَجَابَهُ، فَحَمَلَ القُضَاةُ عَلَى قَوْلِهِ»

“Al-Walīd (the Umayyad governor/caliph) wrote to Khālid ibn Maʿdān regarding a legal matter; he replied, and the judges ruled according to his opinion.”

(Siyar, vol. 5, p. 439)

We also read Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ (vol. 4, p. 538)

“قال الهيثم، والمدائني، وابن معين، والفلاس، وعدة: مات خالد بن معدان سنة ثلاث ومائة. ورُوي عن خالد بن معدان أنه قال: أكل وحمد خير من أكل وصمت. وقال أيضًا: كان سبب إتياننا عنده بسبب الأوزاعي.”

“It was narrated from Khalid ibn Maʿdān that he said: ‘Eating and praising God is better than eating in silence.’ And also: ‘The reason we approached him was because of Al-Awzāʿī.'”

This passage demonstrates a clear scholarly and political nexus between Khalid ibn Maʿdān and Al-Awzāʿī, one of the leading Syrian jurists of the Umayyad period. The explicit mention that people approached Khalid because of his link to Al-Awzāʿī shows that he was deeply embedded within the Syrian scholarly and political milieu, which was closely aligned with the Umayyad state. The era in which Khalid and Al-Awzāʿī operated was notably anti-ʿAlī (as), as illustrated by Imam Dhahabī’s testimony:

«قال صادق بن عبد الله سَمِعْتُ الأوزاعي يقول: لا نأخذ رواتبنا إلا إذا اعتزلنا عليًا وقلنا عنـه ما يضطرنا»

“Sadiq bin Abdullah said that he heard Al-Awzāʿī say: ‘We do not receive stipends unless we refer to Ali as a hypocrite and distance ourselves from him.’”

(Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 7, p. 130)

This testimony indicates that the Umayyad state actively oversaw the indoctrination of its scholars, making Imam Ali (as) persona non grata. Public disavowal of Ali was essentially a condition for receiving state salaries, and Khalid, as a prominent Syrian jurist, functioned within this system. His integration into this politically and sectarian-controlled scholarly environment highlights the need to critically evaluate single-chain Syrian narrations, particularly those praising Muʿāwiyah and Yazīd, for potential political bias.

Further, Khalid’s legal authority directly influenced Umayyad governance. Al-Dhahabī notes:

«كَتَبَ الوَلِيدُ إِلَى خَالِدِ بْنِ مَعْدَانَ فِي مَسْأَلَةٍ فَأَجَابَهُ، فَحَمَلَ القُضَاةُ عَلَى قَوْلِهِ»

“Al-Walīd (the Umayyad governor/caliph) wrote to Khalid ibn Maʿdān regarding a legal matter; he replied, and the judges ruled according to his opinion.”

(Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 5, p. 439)

Ibn Taymiyyah clarifies the ideological character of the Syrian milieu, stating:

«وكان مِن شِيعَةِ عُثْمَانَ مَن يَسُبُّ عَلِيًّا وَيَجْهَرُ بِذَلِكَ عَلَى المَنَابِر»

“Among the Shiʿat ʿUthmān were those who would insult ʿAlī and proclaim it openly from the pulpits.”

(Minhāj al-Sunnah, vol. 6, p. 201)

Thus, the celebrated Syrian isnād originates precisely in a region Ibn Taymiyyah himself acknowledges was dominated by Shiʿat ʿUthmān—those loyal to the Umayyads and openly hostile to ʿAlī. This aligns with Shiblī Nuʿmānī’s observation:

“Ummayad rulers, for about ninety years… insulted the descendants of Fāṭimah and had ʿAlī openly cursed in Friday sermons. They commissioned hundreds of sayings in praise of Muʿāwiyah.”

(Sīrat al-Nabī, vol. 1, p. 60)

Given that this was the period when ḥadīth compilation began, a solitary Syrian chain—fully Umayyad-aligned—claiming that the army conquering Caesar’s city (i.e., Muʿāwiyah/Yazīd’s expedition) is guaranteed Paradise warrants scepticism under the same principle Fared applies to the Wilāyah ḥadīth: reject narrations when the transmitters are politically or doctrinally aligned to propagate innovation or bias.

Farid cannot have it both ways:

*If political-sectarian bias invalidates the Wilāyah isnād, it invalidates the Caesarea-conquest isnād first.

Reply Two – The narration can be authenticated when assessed against other similar narrations

And when we evaluate the evidence through proper hadith methodology, rather than imagination, the conclusion is clear and unavoidable:

The hadith “Ali is the wali of every believer *after me*” is an authentic Sunni narration with multiple supporting shawāhid. It is not an interpolation, not an exaggeration, and not a sectarian fabrication. Its implications are simply theologically inconvenient for Farid.

Thus Farid’s objection does not stand on isnād, matn, logic, or historical context. It stands only on unevidenced speculation—and collapses immediately when placed beside the actual evidence.

When the relevant Sunni narrations are analysed together, a single coherent picture of ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib’s authority emerges—one that cannot be dismissed through conjectural objections or selective weakening of narrators. Each narration highlights a distinct layer of post-Prophetic authority, and when combined, they form a complete doctrinal structure firmly grounded in Sunni ḥadīth literature.

The foundation is the Prophet’s own status as the walī of every believer. We have already proven how Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (6745) preserves the defining principle:

النبي أولى بكل مؤمن من نفسه

“The Prophet is more entitled to every believer than his own self.”

(Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Kitāb al-Ashrāf, Hadith 6745)

This establishes the Qur’anic and Prophetic model of wilāyah: an authority that supersedes even the believer’s authority over himself. Any discussion of succession must begin by identifying who inherits this divinely mandated authority after the Prophet’s departure.

A second narration clarifies that this authority is not open to all companions; it is restricted to a single individual. Sunan al-Tirmidhī (3719) records:

عَلِيٌّ مِنِّي وَأَنَا مِنْ عَلِيٍّ، وَلَا يُؤَدِّي عَنِّي إِلَّا أَنَا أَوْ عَلِيٌّ

“ʿAlī is from me and I am from ʿAlī, and none shall represent me except myself or ʿAlī.”

(Sunan al-Tirmidhī, Kitāb al-Fada’il, Hadith 3719)

Here, representation (yuʾaddī ʿannī) refers to the execution of the Prophet’s delegated religious authority, not mere transmission of information. The Prophet restricts this function exclusively to himself and ʿAlī, meaning that no other Companion may act on his behalf in matters requiring authoritative, prophetic representation. The recurring wording عَلِيٌّ مِنِّي وَأَنَا مِنْ عَلِيٍّ reinforces the spiritual and functional unity between the Prophet and ʿAlī, a principle confirmed in multiple narrations, including the posthumous authority conveyed at Ghadīr Khumm.

Building on this, the third narration specifies that this authority continues after the Prophet’s passing. Ibn Abī Shaybah (Muṣannaf, 12:78, Hadith 12169), al-Ṭabarānī (al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr, 11:62, Hadith 11089), and al-Ḥākim (al-Mustadrak ʿalā al-Ṣaḥīḥayn, 3:132, Hadith 4576) report, through a chain graded ḥasan by Dr. Qāsim al-Jawābrah (Kitāb al-Sunnah, vol. 1, pp. 799–800) and al-Albānī (Ẓilāl al-Jannah, vol. 2, p. 565):

حدثنا محمد بن المثنى، قال: حدثنا يحيى بن حماد، قال: حدثنا أبو عوانة، عن يحيى بن سليم أبي بَلج، عن عمرو بن ميمون، عن ابن عباس، قال:

قال رسول الله ﷺ لعليٍّ:

أنت مني بمنزلة هارون من موسى، إلا أنك لست نبيّاً، وأنت خليفتي في كل مؤمنٍ من بعدي.

Muḥammad ibn al-Muthannā → Yaḥyā ibn Ḥammād → Abū ʿAwānah → Yaḥyā ibn Sulaym (Abū Balj) → ʿAmr ibn Maymūn → Ibn ʿAbbās

“You are to me as Hārūn was to Mūsā, except that you are not a prophet, and you are my khalīfa over every believer after me.”

All narrators in this chain appear in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim except Abū Balj, whose reliability we have already addressed and fully established. Opponents’ selective targeting of him is methodologically baseless, and even ignoring his grading, the matn itself forces a conclusive reading.

The Ghadīr Khumm narration, cited by Zubayr ʿAlī Zai (Tahqiqi Islahi Aur Ilmi Makalaat, Vol. 3, p. 601) from Ibn Hajar (Al-Matalib al-‘Aliyah, 8:390, Hadith 3943–6, graded ṣaḥīḥ), further confirms this authority:

“The Prophet ﷺ came to a tree at Khumm, then came out holding the hand of ʿAlī (ra) and said: ‘Do you not bear witness that Allah, Blessed and Exalted, is your Lord?’ They replied, ‘Yes, we bear witness.’ He then asked, ‘Do you not bear witness that Allah and His Messenger have greater authority over you than your own selves, and that Allah and His Messenger are your guardians (awliyā’)?’ They said, ‘Yes.’ He then said, ‘So whomever Allah and His Messenger are the Mawla of — this (ʿAlī) is his Mawla. And I am leaving among you that which, if you hold fast to it, you will never go astray: the Book of Allah and my Ahl al-Bayt.’”

This full wording preserves the sequence and gravity of the declaration. The Prophet ﷺ first establishes his own legal and executive authority using the Qurʾānic term awlā, then immediately transfers this authority to ʿAlī (as) using the term mawlā.

Friendship requires no legal premise, no public affirmation, and no divine invocation of support or opposition. The public ratification and invocation in Ghadīr signal formal succession and executive authority.

The principle aligns with Qurʾānic usage: walī in governance and guardianship contexts denotes awlawiyyah (pre-eminence) and taṣarruf (executive authority). Classical linguists such as Rāghib al-Iṣfahānī, in Mufradāt al-Qurʾān (Vol. 2, p. 577) and Imam Abu al-ʿAbbās al-Mubarrad clarifies in Kitāb al-Muqtaḍā (vol. 1, p. 112) affirm that walī (with fatḥah) indicates one entrusted with managing affairs and possessing binding decision-making power.

When read together, these narrations do not merely align—they interlock. Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī defines the nature of the Prophet’s authority; Sunan al-Tirmidhī identifies the exclusive executor; Ibn Abī Shaybah, al-Ṭabarānī, al-Ḥākim, and Ghadīr Khumm specify the post-Prophetic officeholder.

• Walī clarifies the scope of authority.

• Yuʾaddī ʿannī (representation) defines its operational execution.

• Khalīfa identifies the successor after the Prophet.

• The recurring phrase عَلِيٌّ مِنِّي وَأَنَا مِنْ عَلِيٍّ underscores the spiritual and functional unity legitimizing ʿAlī’s succession.

Any attempt to dismiss the phrase “after me” collapses under multiple independent Sunni chains, strong narrator credibility, and cross-textual consistency. Fabricators cannot independently produce the same temporal marker, universal authority, and exclusive executor across unrelated transmissions, books, and companions. The evidence is consistent, convergent, and unavoidable: ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib عليه السلام is the Prophet’s exclusive representative, inheritor of his wilāyah, and khalīfa over every believer. Conjecture and theological discomfort have no bearing; the textual and isnād evidence speaks unambiguously.

Even if—purely for argument’s sake—we assumed that “after me” was a Shīʿī addition, the shortest, undisputed wording of Hadith al-Wilāyah still supports the same conclusion. The truncated form, من كنتُ وليَّهُ فَعَلِيٌّ وَلِيُّهُ, cannot coherently be restricted to the Yemen expedition. The Prophet ﷺ chose universal, timeless wording, indicating an enduring authority:

“Whoever I am the Wali of, Ali is his Wali.”

The linguistic and grammatical structure reinforces this:

• من (“whoever”) is universal, not restricted to a particular group.

• كنت in a conditional clause expresses a general principle.

• فعليٌّ وليُّه is present-tense, signalling ongoing, not temporary, wilāyah.

A logical analogy illustrates this: a head of state clarifying authority during a specific mission would say, “During the operation, General X was your commander.” But a universal declaration—“Whoever recognises my authority, General X is his authority”—cannot be interpreted as temporary.

This is precisely the case with the Prophet ﷺ. The combination of universal conditional phrasing and present-tense nominal structure establishes enduring authority. Farid’s attempt to confine it to Yemen collapses under linguistic, rational, and contextual scrutiny.

in conclusion, the evidence from multiple Sunni chains, cross-textual verification, and linguistic analysis converge on one unambiguous truth: ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib عليه السلام is the Prophet’s exclusive representative, inheritor of his wilāyah, and khalīfa over every believer after him.

Fifth Attempt – Accepting this contradicts the ijmāʿ of the Ṣaḥāba

In Sunni legal theory, ijmāʿ is authoritative only when it is established independently. It cannot be invoked to declare an authenticated Prophetic report fabricated, because the hadith corpus itself is one of the primary means by which early agreement or disagreement is known. To appeal to a presumed consensus in order to nullify established narrations therefore assumes the conclusion in advance and then dismisses the very evidence that would challenge it. This is circular reasoning, not principled methodology.

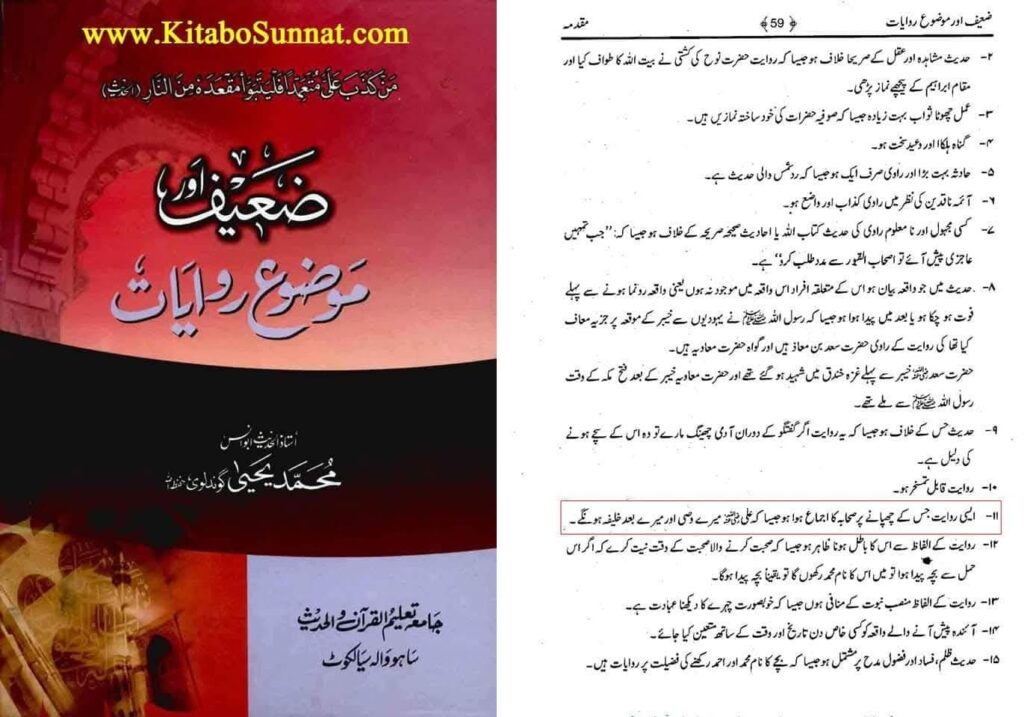

Nevertheless, some Sunni scholars explicitly reject narrations affirming Imam ʿAli ibn Abi Talib’s (ʿa) guardianship and caliphate such as Hadith Wilāyah on precisely these grounds. The Deobandi scholar Muhammad Zakariyya al-Kandhlawi, in Daʿīf wa Mawḍūʿ Riwayāt (p. 59),

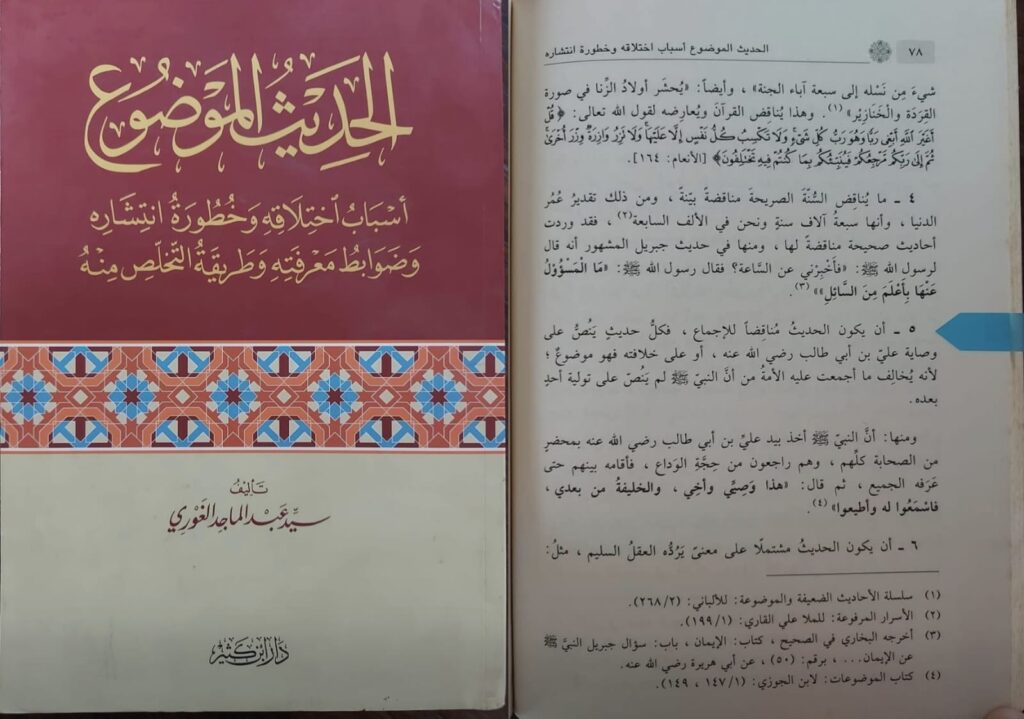

categorises such reports as fabricated on the basis that they “contradict the ijmāʿ of the Ṣaḥāba,” including narrations stating: “After me, ʿAli will be the Walī and Khalīfa.” Similarly, the contemporary Sunni scholar Sayyid Abdul-Majid al-Ghuri, in Al-Ḥadīth al-Mawḍūʿ (p. 78),