According to the Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (3rd ed., p. 1009), the word walī possesses multiple meanings, including: helper, supporter; patron, protector; legal guardian; custodian; manager of affairs; ruler; master; owner; successor (walī al-ʿahd); benefactor.

This range naturally raises an interpretive question:

When the Prophet (s) speaks of wilāyah, which of these meanings does he intend?

Arabic does not permit meanings to be selected arbitrarily. Words with multiple meanings are interpreted by context, usage, and—most decisively—the speaker’s own clarification. In this case, the Prophet ﷺ explicitly defined his own wilāyah over the believers, leaving no ambiguity.

The Prophet’s (s) Wilāyah over the Ummah

The trilateral root w-l-y conveys nearness coupled with responsibility. Classical lexicographers explain that its meanings converge around authority, priority, and guardianship, even when they differ in application.

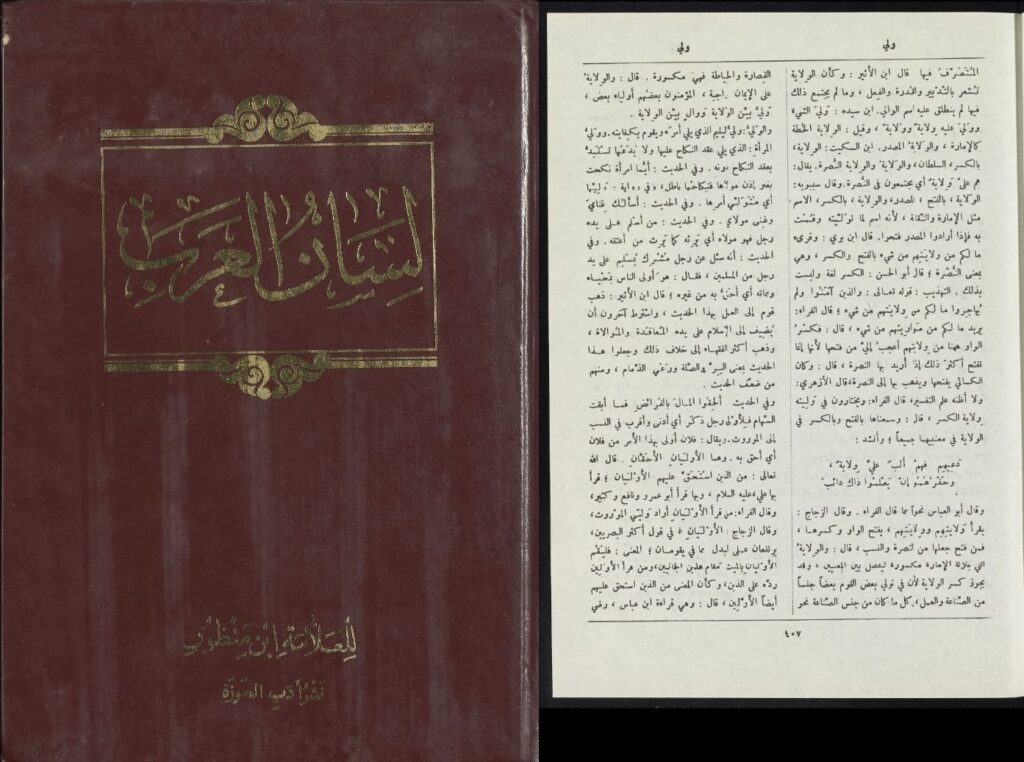

Ibn Manẓūr defines walī as:

وَالْوَلِيّ: وَلِيُّ الأَمْرِ الَّذِي يَلِي أَمْرَهُ وَيَقُومُ بِكِفَايَتِهِ

“The walī is the one who assumes responsibility over an affair and fulfills its obligations.”

(Lisān al-ʿArab, vol. 15, p. 407)