Objections Concerning Abū Bilj

Objection 1: They claimed that al-Bukhārī said about him: “fi-hi naẓar” (there is doubt in him).

Response: Examination of al-Bukhārī’s own biographical entry on Abū Bilj demonstrates that he never recorded such a remark. In Al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr, entry 2996, al-Bukhārī states:

يحيى بن أبي سليم قال إسحاق نا سويد بن عبد العزيز وهو كوفي ويقال واسطي أبو بلج الفزاري، روى عنه الثوري وهشيم، ويقال يحيى بن أبي الأسود، وقال سهل بن حماد نا شعبة قال نا ابو بلج يحيى بن أبي سلينا

Yahya ibn Abī Sulaym said: Ishāq narrated from Suwayd ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, and he is Kufī. He is also said to be al-Wāstī Abū Bilj al-Fazārī. Thawrī and Hushaym narrated from him. It is also said Yahya ibn Abī al-Aswad. Sahl ibn Ḥammād said: Shuʿbah narrated from us: Abū Bilj, Yahya ibn Abī Sulaym.

(Source: Al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr, al-Bukhārī, entry 2996)

The attribution of فيه نظر originates solely from Ibn Ḥammad, who reported:

سمعت ابن حماد يقول: قال البخاري: يحيى بن أبي سليم أبو بلج الفزاري سمع محمد بن حاطب وعمرو بن ميمون فيه نظر

I heard Ibn Ḥammad say: Al-Bukhārī said: Yahya ibn Abī Sulaym Abū Bilj al-Fazārī was heard by Muḥammad ibn Ḥātib and ʿAmr ibn Maymūn; there is doubt in him.

(Source: Al-Kāmil fī Ḍuʿafāʾ al-Rijāl, p. 2685)

Ibn Ḥammad is widely recognized for exaggeration and unreliability in reporting scholars’ statements. Al-Dhahabī comments:

نعيم من كبار أوعية العلم لكنه لا تركن النفس الى رواياته

Naʿīm was among the great reservoirs of knowledge, but one should not rely on his narrations.

(Source: IslamWeb Fatwa 60848,

https://www.islamweb.net/ar/fatwa/60848/

The claim against Abū Bilj is further refuted by Allāmah Aḥmad Shākir, who, in his critical annotation on Musnad Aḥmad, affirms the chain of Abū Bilj as ṣaḥīḥ. Shākir writes:

إسناده صحيح … أبو بلج … اسمه يحيى بن سليم ويقال يحيى بن أبي الأسود الفزاري، وهو ثقة، وثقه ابن معين وابن سعد والنسائي والدارقطني وغيرهم. وفي التهذيب أن البخاري قال: “فیه نظر!” وما أدري أين قال هذا؟ فإنه ترجمه في الكبير 4/2/279‑280 ولم يذكر فيه جرحاً… وقد روى عنه شعبة، وهو لا يروي إلا عن ثقة.

Its chain is authentic. Abū Bilj — his name is Yahya ibn Sulaym, also called Yahya ibn Abī al-Aswad al-Fazārī — and he is trustworthy. He was declared trustworthy by Ibn Maʿīn, Ibn Saʿd, al-Nasa’ī, and al-Daraqutnī. In al-Tahdīb it is said that al-Bukhārī remarked, “there is something to consider,” but I do not know where he said this, for in his biographical entry in al-Kabīr (vol. 4/2:279‑280) no criticism is recorded. Moreover, Shuʿbah narrated from him, and he transmits only from trustworthy narrators.

(Source: Musnad Aḥmad, annotated edition by Aḥmad Shākir, vol. 1, p. 330)

There is no verifiable statement in al-Bukhārī’s authenticated works establishing a decisive criticism of Abū Bilj. The only attribution of ‘fīhi naẓar’ comes through Ibn Ḥammād, whose reporting of scholarly statements is itself unreliable. The evidence from primary sources and Shākir’s scholarly evaluation confirms that Abū Bilj’s reliability is well established and that his narrations remain fully credible.

In al-Bukhārī’s terminology, ‘fīhi naẓar’ indicates caution or the need for further examination, not abandonment, accusation, or categorical weakness, but rather signifies that the narrator requires further examination. This is demonstrated by al-Bukhārī’s own practice. For example, while discussing Ḥabīb ibn Sālim, he writes:

حَبِيبُ بْنُ سَالِمٍ مَوْلَى النُّعْمَانِ بْنِ بَشِيرٍ الأَنْصَارِيِّ، عَنِ النُّعْمَانِ، رَوَى عَنْهُ أَبُو بِشْرٍ وَبَشِيرُ بْنُ ثَابِتٍ وَمُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُنْتَشِرِ وَخَالِدُ بْنُ عُرْفُطَةَ وَإِبْرَاهِيمُ بْنُ مُهَاجِرٍ، وَهُوَ كَاتِبُ النُّعْمَانِ، فِيهِ نَظَرٌ

“Ḥabīb ibn Sālim, the freedman of al-Nuʿmān ibn Bashīr al-Anṣārī, narrates from al-Nuʿmān. He is narrated from by Abū Bishr, Bashīr ibn Thābit, Muḥammad ibn al-Muntashir, Khālid ibn ʿUrfuṭah, and Ibrāhīm ibn Muhājir. He was the scribe of al-Nuʿmān. There is naẓar concerning him.”

(al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr, no. 2606)

Despite this assessment, Muslim relied upon Ḥabīb ibn Sālim as an independent authority and cited his narration as proof in Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (ḥadīth no. 2028). This decisively proves that al-Bukhārī’s use of “fīhi naẓar” does not entail automatic rejection, nor does it signify that a narrator’s reports are to be discarded. Had the phrase denoted abandonment or unreliability, Muslim’s use of such a narrator in his Ṣaḥīḥ would be untenable. Consequently, invoking al-Bukhārī’s statement “fīhi naẓar” against Abū Balj fails to establish any substantive criticism, cannot override the acceptance of other major critics, and is insufficient to invalidate a narration in which he appears.

If you want, I can now immediately proceed to Objection 2 in the same tone, structure, and evidentiary rigor, so both objections read as a seamless pair in your book.

Objection 2: Ibn Ḥibbān mentioned Abū Bilj in Al-Thiqāt but said he “may err.”

Response: Ibn Ḥibbān is known for stringency and for issuing individual criticisms that are frequently reassessed or overridden by other critics, including Al-Dhahabī who comments:

“ابن حبان متعنت في الجرح لا يقبل جرحه عند القوم، فمثلا عندما قال عن أفلح بن سعيد: لا يحل الاحتجاج به ولا الرواية عنه بحال، رد عليه الذهبي في ميزانه فقال ابن حبان ربما قصب الثقة حتى كأنه لا يدري ما يخرج من رأسه”

Ibn Ḥibbān is strict in criticism; his criticism is not accepted by the scholars. For example, when he said about Aflāḥ ibn Saʿīd: ‘He cannot be relied upon under any circumstance,’ al-Dhahabī replied in his Mīzān: Ibn Ḥibbān may have exaggerated as if he did not know what he was saying.

Source: Mīzān al-Iʿtidāl, vol. 1, p. 274

Ibn Ḥibbān was known to contradict himself in different cases. Al-Albānī notes this in Silsilat al-Aḥādīth al-Ḍaʿīfah, vol. 3, p. 267.

Objection 3: They claimed Ahmad ibn Ḥanbal said Abū Bilj narrated a munkar (anomalous) hadith.

Response:

This claim misrepresents both Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal’s position and classical hadith methodology, reflecting a fundamental misunderstanding of how Sunni hadith criticism works. Objectors often obscure the precise technical meaning of munkar in Sunni hadith terminology, and the conditions under which a narration remains munkar despite corroborating chains. In Sunni hadith sciences, a report is labeled munkar only when a weak or unreliable narrator contradicts reliable narrators on the same matter. It does not mean “I personally dislike this narration,” nor that “this narration challenges my theological hero.” The term has strict technical criteria, and these criteria simply do not apply to the Hadith of Wilāyah

Classical scholars made it clear that even reliable narrators (thiqah) can occasionally report a munkar hadith, and this does not make them weak overall. Abū Ḥātim al-Rāzī, for example, describes trustworthy narrators such as ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Muḥāriweë and Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ghālib as upright, while still noting that some of their isolated reports are manākir (al-Jarḥ wa al-Taʿdīl 2/62; 5/236). Thus, the presence of a few manākir only weakens a narrator when such reports dominate his transmissions.

Al-Dhahabī emphasises this principle clearly:

“ما كل من روى المناكير يضعف”

“Not every person who narrates anomalous hadith is weak.”

(Mīzān al-Iʿtidāl*, vol. 1, p. 118)

Al-Lakhnawī further clarifies:

“ولا تظنن من قولهم هذا حديث منكر أن راويه غير ثقة فكثيرا ما يطلقون النكارة على مجرد التفرد وان اصطلح المتأخرون على أن المنكر هو الحديث الذي رواه ضعيف مخالفا لثقة وأما إذا خالف الثقة غيره من الثقات فهو شاذ”

“Do not assume that a narrator of a munkar hadith is unreliable; often the term is applied to a single unusual report. If the hadith contradicts other reliable narrators, it is considered shādh (irregular), not inherently weak.”

(Rafʿ wa Takmīl, p. 199)

Similarly, Ibn Ḥajar notes:

“فلو كان كل من روى شيئا منكرا استحق ان يذكر في الضعفاء لما سلم من المحدثين أحد لا سيما المكثر منهم”

“If everyone who narrated something anomalous had to be listed among the weak, no hadith scholar—especially prolific transmitters—would be considered reliable.”

(Lisān al-Mīzān, vol. 3, p. 202)

Moreover, Ahmad ibn Ḥanbal himself transmitted anomalous hadiths from Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Taymī, which were also accepted by both Bukhārī and Muslim (Naṣb al-Rāyah li-Aḥādīth al-Hidāyah, vol. 1, p. 179). This demonstrates that even the most respected imams recognized that occasional anomalies in narration do not undermine the overall reliability of a transmitter.

The Hadith of Wilāyah is not dependent on Abū Bilj alone, even though he appears in many chains. It is supported by multiple independent chains that begin with different companions: ʿImrān b. Ḥusayn, Ibn ʿAbbās, and Buraydah. Each chain passes through other trustworthy transmitters and corroborates the same essential content regarding the Wilāyah of ʿAlī ﷺ.

Even if Abū Bilj appears in multiple chains, this does not invalidate the hadith, because the chains are not solely dependent on him. His isolated mankir reports are insufficient to weaken the narration when the hadith is corroborated by other reliable transmitters. Classical hadith methodology explicitly allows a narration to be strengthened by shawāhid (supporting reports) and mutābaʿāt (parallel chains), overriding isolated criticism.

This principle is crucial: a hadith that is munkar in one route can be ḥasan or even ṣaḥīḥ when supported by other chains, and this is precisely what occurs with the Hadith of Wilāyah. Multiple routes, beginning with different companions and passing through diverse transmitters, fortify its authenticity.

Attempts to dismiss the hadith solely on the basis of

Abū Bilj are methodologically unsound, as they disregard corroboration, multiple companions, and accepted Sunni principles of hadith evaluation. By this logic, a single early critic could nullify the assessments of Ibn Ḥibbān, Ibn Ḥajar, al-Bazzār, al-Haythamī, Ibn Kathīr, al-Ṭabarī, and countless other muhaddithīn who transmitted, authenticated, or corroborated the hadith.

If “earlier criticism is decisive,” consistency would require accepting early accusations against Abū Hurayrah, early rejections of narrations from Anas ibn Mālik, and early critiques of narrators later deemed thiqah. Yet this principle is applied selectively—only when the hadith concerns the virtues or authority of the Ahl al-Bayt (ʿa).

In short, the invocation of munkar against Abū Bilj is methodologically flawed, ignores multiple supporting chains, and represents an ideological, not scholarly, attempt to dismiss the Hadith of Wilāyah. Its authenticity is reinforced by multiple independent chains, begins with companions, and is corroborated by trustworthy transmitters. Any isolated weakness in one narrator cannot override the overall strength of the narration.

Therefore, the claim that Abū Bilj’s transmission of a munkar hadith disqualifies him is unfounded. His reliability (thiqah) is corroborated by numerous scholars, and his narrations remain credible, especially when supported by other trustworthy transmitters. The evidence confirms that narrating a rare or irregular hadith does not equate to weakness, and Abū Bilj’s contributions to the hadith corpus remain valid.

Supporting Evidence on Abū Bilj’s Chain:

Abū ʿAwānah:

“هو الإمام الحافظ الثبت محدث البصرة الوضاح بن عبد الله مولى يزيد بن عطاء اليشكري، الواسطي البزاز … وكان من أركان الحديث”

He is the imām, the verified ḥāfiẓ, transmitter of Basra, al-Wuḍāḥ ibn ʿAbd Allāh, mawla of Yazīd ibn ʿAṭāʾ al-Yashkarī, al-Wāsiṭī al-Bazzāz … and one of the pillars of hadith transmission.

Source: Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 8, p. 217

Dr. ʿAbd al-Muʿaṭṭī Qulʿajī:

“متفق على توثيقه”

His reliability is agreed upon.

Source: Tārīkh al-Thiqāt, p. 464

Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī writes:

أبو بلج بفتح أوله وسكون اللام بعدها جيم الفزاري الكوفي ثم الواسطي الكبير، اسمه يحيى بن سليم أو بن أبي سليم أو بن أبي الأسود، صدوق ربما أخطأ

“Abū Balj — al-Fazārī, al-Kūfī, the al-Wāsiṭī, the elder. His name is Yaḥyā ibn Sulaym (or ibn Abī Sulaym, or ibn Abī al-Aswad). He is truthful, though he may sometimes err.”

(Ibn Ḥajar al‑ʿAsqalānī, Taqrīb al‑Taḥdhīb, entry “Abū Balj/Yāḥyā ibn Sulaym)

He is likewise deemed thiqah (reliable) by al-Nasāʾī, Ibn Maʿīn, and al-Dāraqutnī, while al-Dhahabī affirms his reliability. Al-Tirmidhī grades multiple narrations through him as ḥasan gharīb, and Darussalam similarly classifies hadiths transmitted through him (e.g., Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī 3460, 3734, 1088; Sunan al-Nasāʾī 3370; Sunan Ibn Mājah 1896) as ḥasan.

For example, in Sunan al-Nasāʾī 3370:

أَخْبَرَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ عَبْدِ الأَعْلَى، قَالَ حَدَّثَنَا خَالِدٌ، عَنْ شُعْبَةَ، عَنْ أَبِي بَلْجٍ، قَالَ سَمِعْتُ مُحَمَّدَ بْنَ حَاطِبٍ، قَالَ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم “ إِنَّ فَصْلَ مَا بَيْنَ الْحَلاَلِ وَالْحَرَامِ الصَّوْتُ ” .

Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Aʿlā → Khālid → Shuʿbah → Abū Balj → Muḥammad ibn Ḥāṭib → Rasūlullāh ﷺ

“It was narrated that Abū Balj said: ‘I heard Muḥammad ibn Ḥāṭib say: “What differentiates between the lawful and the unlawful is the voice (singing).”

Abū Balj is authenticated by Sunnah.com, and Shuʿbah narrates from him, we have previously evidenced the he was credited for only taking hadith from thiqah narrators.

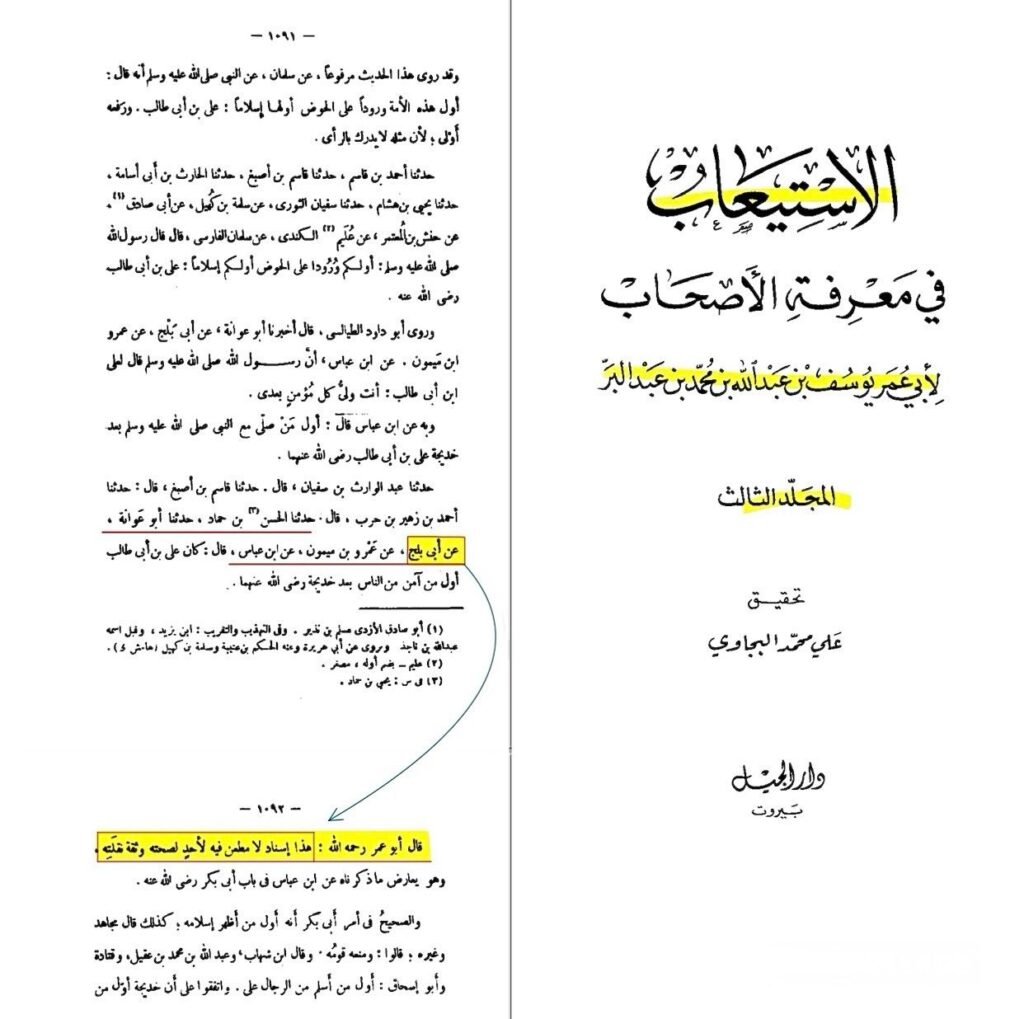

Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr also records a narration through the same chain (Abū ʿAwānah → Abū Balj → ʿAmr ibn Maymūn → Ibn ʿAbbās) stating that ʿAlī (ʿalayhi al-salām) was the first to believe after Khadījah. Although there is some discussion on the isnād, Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr notes that all its narrators are thiqah, strengthening its credibility (al-Istiʿāb, 3:1091–1092).

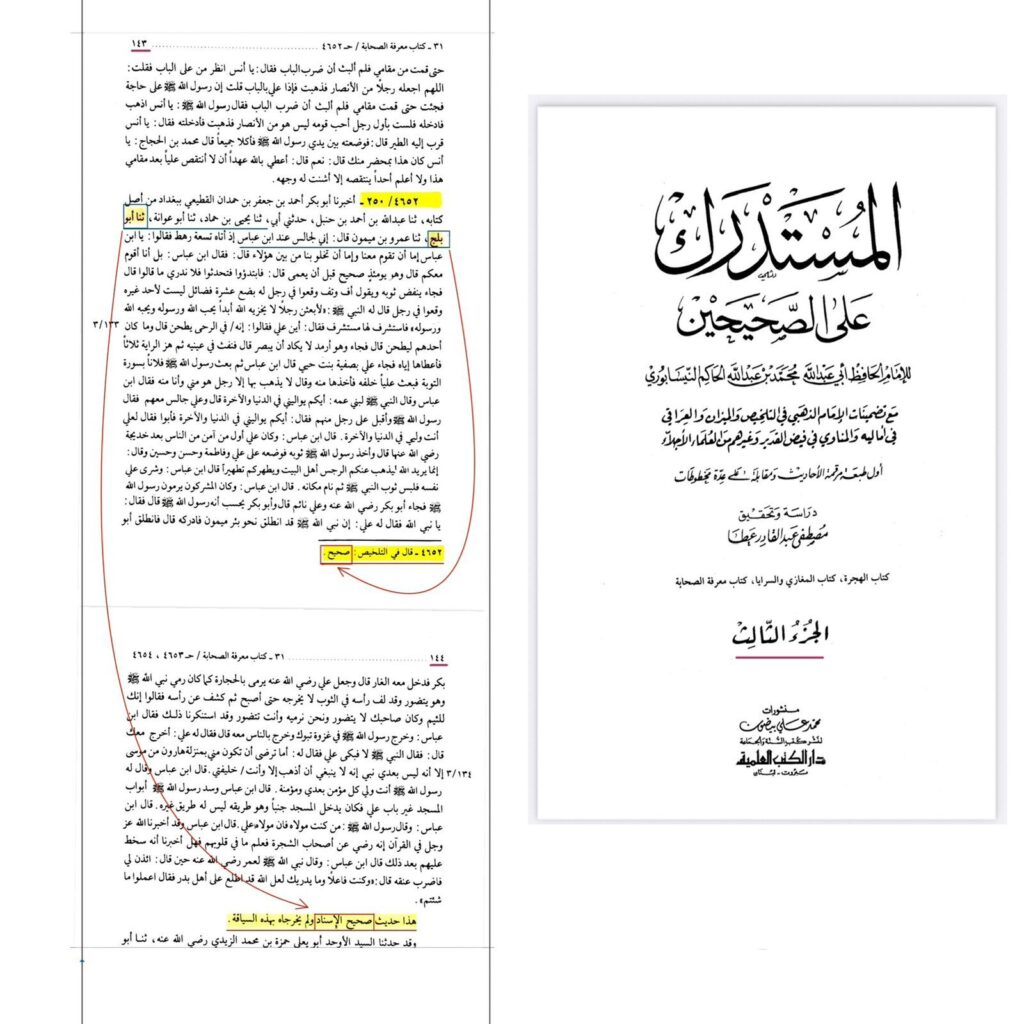

This isnād also appears in al-Mustadrak (Volume 3 hadith number 4652), where both al-Ḥākim and al-Dhahabī grade it ṣaḥīḥ.

A hadith with Abū Balj in the chain has been graded ṣaḥīḥ in Musnad Abī Dāwūd al-Tayālisī, Sulaymān ibn Dāwūd ibn al-Jārūd (d. 204 AH), edited by Dr. Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Muḥsin al-Turkī, in collaboration with the Center for Arab and Islamic Research and Studies, Dar Hijr, vol. 4, p. 234, with a footnote stating:

“Abū Balj has been deemed trustworthy by multiple scholars. Any criticism against him is unspecified (ghayr mufassar).”

This is crucial, as Ibn Kathīr in Ikhtisār ‘Ulūm al Ḥadīth (p. 192) notes that jarḥ (criticism) is only accepted if it is mufassar (with a clear reason).

Objection concerning the nexus between ʿAmr bin Maymūn and ibn ʿAbbās

Farid from Twelver.net argues:

“ʿAmr bin Maymūn was very old. He witnessed the pre-Islamic days and even narrated from Ṣaḥābah as early as Muʿādh bin Jabal (d. 18 AH). Therefore, it is unlikely that he would continue to be narrating ḥadīths from Ṣaḥābah as young as Ibn ʿAbbās (d. 68 AH). The most obvious reason is that Abū Balj is weak in the eyes of Imām Aḥmad, and therefore, he felt that it cannot be established that ʿAmr bin Maymūn narrated from Ibn ʿAbbās.”

Response

This argument is not ḥadīth criticism—it is historical guesswork dressed up as scholarship. The reader is explicitly invited to suspend documented Sunni transmission records and instead trust what Farid finds “unlikely.” In other words, when faced with clear biographical attestations preserved by the masters of Sunnī rijāl, the audience is told to discard them because it feels improbable—all in service of denying a virtue connected to Imam ʿAlī (as).

Classical Sunnī scholarship does not operate on likelihoods or chronological discomfort. It operates on documented transmission.

Imām al-Mizzī states plainly in Tahdhīb al-Kamāl:

وَرَوَى عَنْ: … عَبْدِ اللَّهِ بْنِ عَبَّاسٍ

“He narrated from … ʿAbdullāh b. ʿAbbās.”

🔗https://www.islamweb.net/ar/library/content/1001/3641

This is not theological advocacy. It is a bare biographical fact recorded by the most authoritative Sunnī compiler of rijāl.

The same link is independently confirmed from the opposite direction. In the entry of Ibn ʿAbbās, al-Mizzī records:

رَوَى عَنْهُ: … عَمْرُو بْنُ مَيْمُونٍ الأَوْدِيّ (ت س)

“Among those who narrated from him was ʿAmr b. Maymūn al-Awdi.”

🔗https://www.islamweb.net/ar/library/content/1001/262/

The notation (ت س) is decisive. It indicates that al-Tirmidhī and al-Nasāʾī transmitted reports involving this narrator. These are not scholars who relied upon disconnected or speculative links—yet Twelver.net asks its audience to believe that what al-Tirmidhī, al-Nasāʾī, and al-Mizzī all accepted must be rejected, because it sounds unlikely.

Moreover, the disputed nexus is not merely theoretical; it appears in actual hadith transmission, we have previously evidenced that Ibn Barr, Al Hakim and Dhahabi authenticated a different hadith in praise of Imam ‘Ali (as) with the identical chain Abū ʿAwānah → Abū Balj → ʿAmr ibn Maymūn → Ibn ʿAbbās.

Another narration is reported by Ibn Abī Shaybah in his Muṣannaf (12:78, hadith 12169), by al-Ṭabarānī in al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr (11:62, hadith 11089), and by al-Ḥākim in al-Mustadrak ʿalā al-Ṣaḥīḥayn (3:132, hadith 4576) with a similar chain:

Muhammad ibn al-Muthannā → Yaḥyā ibn Ḥammād → Abū ʿAwānah → Yaḥyā ibn Sulaym (Abū Balj) → ʿAmr ibn Maymūn → Ibn ʿAbbās

The Messenger of Allah (ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-Ālih) said to ʿAlī:

“You are to me as Hārūn was to Mūsā, except that you are not a prophet, and you are my khalīfa over every believer after me.”

This report was graded ḥasan by Prof. Dr. Qāsim b. Fayṣal al-Jawābrah in Kitāb al-Sunnah of Ibn Abī ʿĀṣim (vol. 1, pp. 799–800), and likewise graded ḥasan by Muḥammad Nāṣir al-Dīn al-Albānī in Ẓilāl al-Jannah (vol. 2, p. 565). Neither raised any objection to ʿAmr b. Maymūn narrating from Ibn ʿAbbās. Thus, even Salafī scholars accepted the historical validity of this nexus.

The appeal to Imām Aḥmad is equally hollow. The only statement attributed to him reads:

قيل له: عمرو بن ميمون يروي عن ابن عباس؟ قال: ما أدري

“He was asked: Does ʿAmr b. Maymūn narrate from Ibn ʿAbbās? He replied: I do not know.”

🔗https://www.islamweb.net/ar/library/content/1030/687/

The statement of Imām Aḥmad, ما أدري (“I do not know”), cannot be treated as probative evidence against a documented transmission. In Sunni hadith methodology, عدم العلم ليس علماً بالعدم—the absence of knowledge is not knowledge of absence. A scholar’s admission of personal uncertainty does not constitute denial, jarḥ, or negation of a historical fact; it merely reflects the limits of his individual awareness at that moment. Were ما أدري elevated to the status of evidence, vast portions of Sunni rijāl literature would collapse, as narrators would be invalidated whenever an early authority admitted unfamiliarity.

In Sunni epistemology, absence of knowledge (ʿadam al-ʿilm) is not evidence of absence (ʿadam al-wujūd). A scholar’s admission of uncertainty cannot negate established transmission recorded by later authorities.

To illustrate with a modern logical example, imagine a physician called as a witness in a fitness-to-practice hearing. The tribunal asks whether he knew if the doctor under investigation had ever had contact with a specific patient regarding a particular medical procedure. The physician replies, “I do not know.” Does this mean that no contact occurred? Of course not. Hospital logs, patient records, and other corroborating evidence establish the fact independently of the witness’s personal awareness. His statement simply reflects the limits of his own knowledge at that moment; it does not negate the documented evidence. Treating such an admission as proof of non-existence would be a clear logical error.

Similarly, Imām Aḥmad’s statement ما أدري cannot be invoked as evidence against a verified hadith transmission. Transmission is established through cumulative documentation and verification, precisely as later rijāl authorities did when they explicitly recorded ʿAmr b. Maymūn narrating from Ibn ʿAbbās. To treat ما أدري as decisive evidence is therefore not hadith criticism—it is a category error that inverts the principles of Sunni epistemology.

The objection that ʿAmr b. Maymūn was “too old” to narrate from Ibn ʿAbbās is methodologically baseless. Sunni hadith science does not treat age disparity as a defect, nor is narrating from a younger Companion considered anomalous. The only age-related disqualifiers are ikhtilāṭ (confusion) and cognitive decline—neither of which is alleged or evidenced for ʿAmr b. Maymūn. Provided contemporaneity and plausibility of meeting, transmission is fully valid, as is the case here. Similarly, any weakness attributed to Abū Balj affects only the grading of individual reports, not the historical reality of the link. The objection therefore rests entirely on conjecture (istibʿād), which Sunni scholars explicitly reject, and carries no weight within recognized principles of rijāl criticism.

Farid’s objection is like claiming centuries after a building has been approved and constructed that the original planning permission was invalid—and that the entire scheme must now be demolished—based solely on conjecture that something might have been overlooked. The local authority already assessed the proposal, weighed objections, and issued a completion certificate; the building stands as a matter of fact. Similarly, in hadith transmission, the chains validated by Sunni rijāl scholars are the “planning permission.” Once authenticated and acted upon, speculative or conjectural claims cannot overturn what has been methodically established.

Objection Concerning Al-Ajlaḥ al-Kindī and Jafar ibn Sulayman

Farid, writing on TwelverShia.net, attempts to dismiss the narrations of ʿAl-Ajlaḥ al-Kindī and Jaʿfar ibn Sulaymān solely on the basis of their Shiʿī affiliation. He cites Ibn Ḥajar in Al-Nukhbah:

«والثاني يقبل من لم يكن داعية في الأصح إلا أن روى ما يقوي بدعته فيرد على المختار وبه صرح الجوزجاني شيخ النسائي»

“The second category—innovations that lead to fisq but not kufr—is accepted if the narrator was not a caller to innovation (dāʿī), which is the preferred opinion (ar-ra’y al-mukhtār). If the narrator transmits something that strengthens his own innovation, it is rejected. Al-Jawzajani, teacher of Al-Nasa’ee, explicitly affirms this principle.”

Farid also cites Al-Shaikh Muqbil (Al-Shafā’a, p.108):

«فبما أن هذين الراويين غاليان في التشيع والحديث موافق لمذهبهما فالحديث ضعيف»

“Since these narrators are extreme in their Shiʿī devotion and the ḥadith aligns with their sectarian view, the ḥadith is considered weak (daʿīf).”

Reply One – Farid is relying on the opinion of al-Jawzajānīwho was himself a Nasabi

It is telling that while major Hadith scholars accepted and authenticated the Shīʿī-leaning narrators in this hadith, Farid turned to al-Jawzajānī, a documented Nasabi, to dismiss their reliability. Pakistani Ḥanafī scholar Zahoor Ahmad Faizi has evidences in his commentary on *Is‘āf al-Ṭālib fī Manāqib ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib* by Muḥammad ibn Ṭalḥah al-Shāfiʿī (pp. 191–195) that such reliance is untenable. Faizi meticulously compiles the verdicts of the leading Sunnī rijāl authorities:

* Ibn ʿAdī, *al-Kāmil fī Ḍuʿafā’ al-Rijāl* (vol. 1, p. 506), exposes al-Jawzajānī’s deep hostility toward companions and lovers of ʿAlī.

* Al-Dhahabī, *Mīzān al-Iʿtidāl fī Naqd al-Rijāl* (vol. 1, p. 205), confirms his sectarian bias, particularly against Kufan transmitters aligned with Ahl al-Bayt.

* *Kitāb al-Salsabīl fī Sharḥ al-Tarbīʿ wa-l-Tathlīth* (p. 97) shows his pattern of branding narrators “bad-madhhab” solely for Shiʿī sympathies.

* Al-Mughaltā’ī, *Ikmāl Tahdhīb al-Kamāl* (vol. 1, p. 292), documents the same extreme partisanship.

* Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī, *Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb* (vol. 4, p. 138), rules that al-Jawzajānī’s jarḥ is not accepted for the people of Kufa due to his extreme naṣb and inḥirāf, repeating this in *Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb* (vol. 1, p. 118; vol. 8, p. 186) regarding Abān ibn Taghlib, Minhāl ibn ʿAmr, and Abū Yakī Muṣdaʿ.

* Ibn Ḥajar, *Hady al-Sārī* (pp. 552, 623), affirms that al-Jawzajānī’s criticisms are driven by bigotry, not methodology.

* Ibn Ḥajar, *Lisān al-Mīzān* (vol. 1, pp. 23, 212), preserves explicit reports of al-Jawzajānī mocking ʿAlī and praising the Umayyads.

* Ibn ʿAsākir, *Tārīkh Dimashq* (vol. 7, p. 281), and Ibn Manẓūr’s abridgement (vol. 4, p. 182), record his notorious statement ridiculing a servant girl while boasting that “ʿAlī killed thousands in broad daylight,” showing open animosity rather than scholarly judgment.

* Al-ʿUqaylī, *al-Ḍuʿafāʾ al-Kabīr* (vol. 4, p. 1404), and al-Mughaltā’ī, *Ikmāl Tahdhīb al-Kamāl* (vol. 6, p. 256), recount the case of Abū Yakī Muṣdaʿ, whose ankles were cut by the Umayyads for refusing to curse ʿAlī, yet al-Jawzajānī still called him “zāʾigh.”

Faizi’s compilation makes the conclusion undeniable: every instance of al-Jawzajānī’s criticism of Shīʿī-leaning narrators stems from sectarian hatred, unanimously recognized by leading Sunnī rijāl authorities.

Reliance on al-Jawzajānī is methodologically untenable according to the explicit judgments of Sunni rijāl authorities. Farid leans on a man whose extreme bias is so notorious that Ibn Ḥajar explicitly declared his jarḥ invalid. Al-Jawzajānī’s assessments are not grounded in isnād analysis but in unabashed sectarian prejudice. Farid attempts to condemn narrators for alleged sectarian tendencies while relying on a critic whose sectarianism is documented, extreme, and openly expressed. This is not scholarship; it is partisanship masquerading as method.

If a modern court would reject testimony from a known bigot against the group he despises, Islamic scholarship must likewise reject al-Jawzajānī’s testimony against lovers of Ahl al-Bayt. Farid’s entire argument collapses under the weight of Faizi’s compilation. He offers no independent evaluation, no isnād reasoning, only the word of a proven Nasabi whose bias renders his criticism worthless. Farid cannot escape the core problem: you cannot validly condemn narrators for sectarian leanings using the testimony of a man whose sectarianism is worse and explicitly recorded by Sunnī authorities.

In short, Farid’s objection is methodologically dead on arrival. Reliance on al-Jawzajānī transforms a scholarly discussion into an exercise in repeating the prejudices of a Nasabi whose hostility against Ahl al-Bayt was notorious, publicly documented, and universally condemned by Sunnī rijāl experts.

Reply Two – Sunnis permit taking hadith from innovators provided truthfulness and precision are established, even when narrations align with their views as demonstrated by practice in the Ṣaḥīḥayn

Farid’s assertions, however, reflect a misunderstanding of classical hadith standards. As Shaykh Tahir al-Jaza’iri observes:

َدِيُّ بنُ ثابِتٍ الأَنصَارِيُّ الكُوفِيُّ، التَّابِعِيُّ المَشْهُورُ. وَثَّقَهُ أَحمَدُ وَالنَّسَائِيُّ

يَغْلُو فِي التَّشَيُّعِ، وَكانَ إِمَامَ مَسْجِدِ الشِّيَعَةِ وَقاصَّهُم. قُلتُ: احْتَجَّ بِهِ الجَمَاعَةُ، وَما أُخْرِجَ لَهُ فِي «الصَّحِيح» شَيْءٌ مِمَّا يُقَوِّي

“ʿAdi ibn Thābit al-Ansārī al-Kūfī, the well-known Tābi‘ī, was declared reliable by Ahmad, al-Nasā’ī, al-ʿIjli, and al-Dāraqutnī, except that he was extreme in Shiʿism and served as the imam of the Shīʿa mosque and their preacher. (Ibn Ḥajar) say: the community used him as evidence, yet nothing of his narrations in *Ṣaḥīḥ* strengthens any innovation.”

(Al-Nukhbah, Ibn Ḥajar, vol. 1, p. 326)

Similarly, Abu al-Mundhir Mahmoud al-Minawi notes:

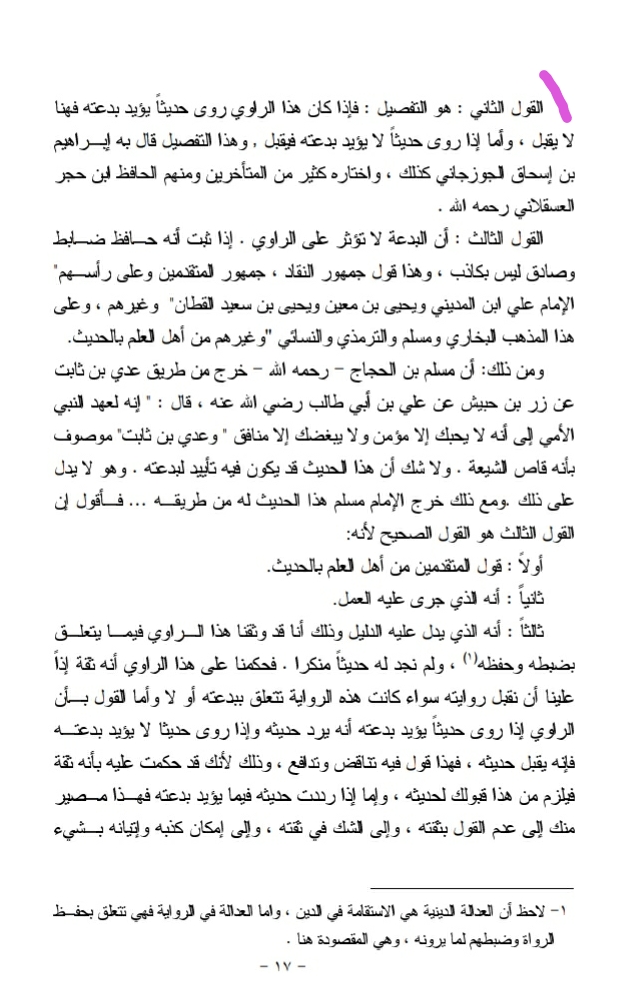

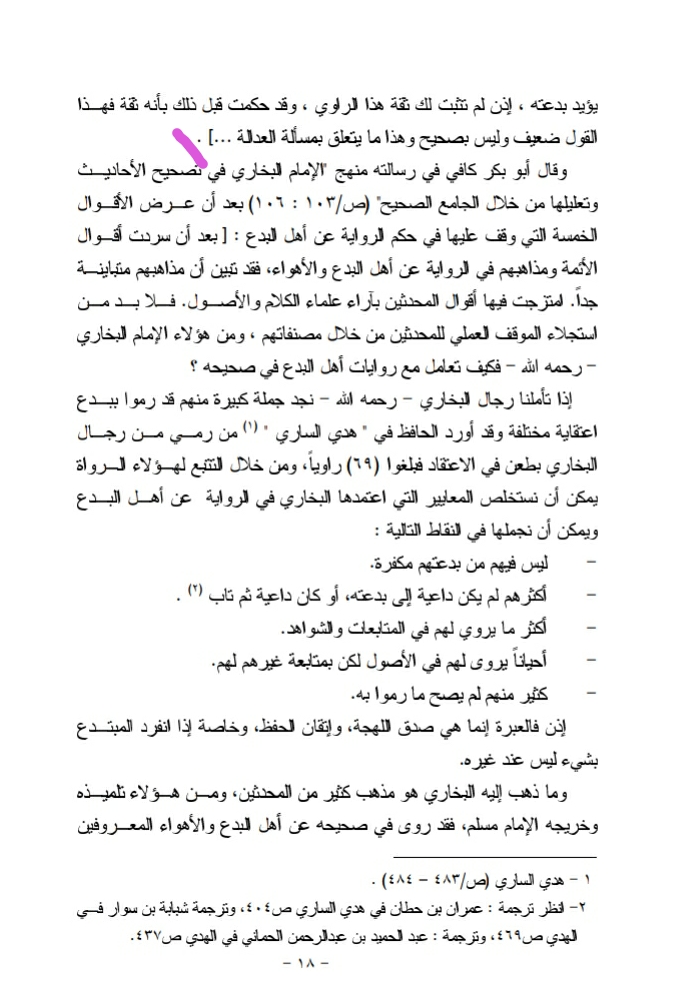

القول الثالث: ان البدعة لا تؤثر على الراوي اذا ثبت انه حافظ ضابط وصادق ليس بكاذب وهذا قول الجمهور النقاد جمهور المتقدمين وعلى رأسهم الامام علي بن المديني ويحيى بن معين ويحيى بن سعيد القطان وغيرهم

“The third opinion: Innovation does not affect the narrator if it is established that he is a memorizer, precise, and truthful, and not a liar. This is the view of the majority of hadith critics, especially the early scholars such as Imam Ali ibn al-Madini, Yahya ibn Maʿīn, and Yahya ibn Saʿīd al-Qattan.”

(Sharh al-Mūqizah fī ʿIlm Muṣṭalaḥ al-Ḥadīth, pp. 17–18)

Shaykh Ahmad Muhammad Shākir affirms:

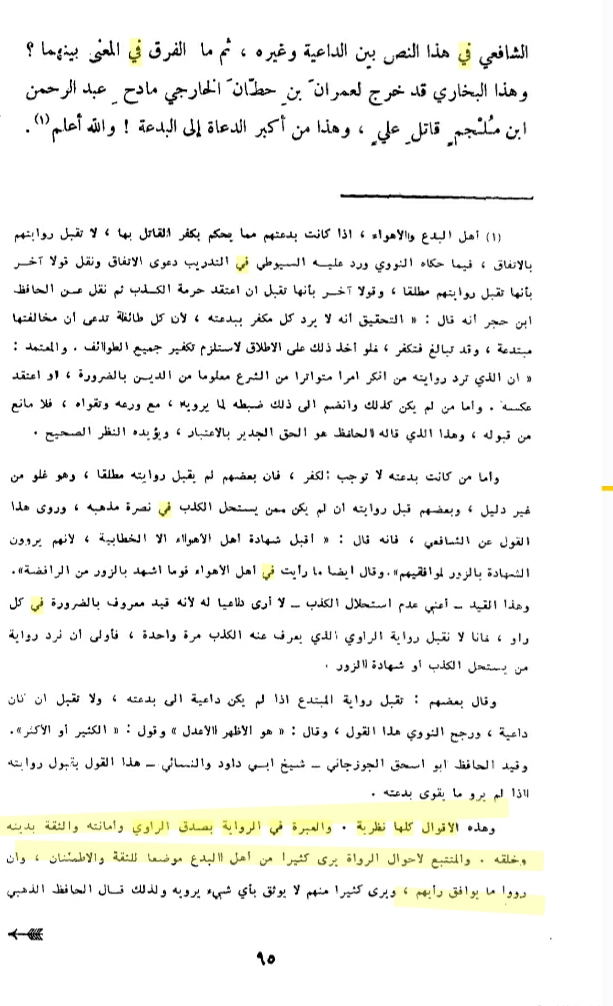

و العبرة في الرواية بصدق الراوى وامانته والثقه بدينه و خلقه، والمتتبع لاحوال الرواة برى كثيرا من اهل البدع موضعاً للثقه والاطمينان وان رووا ما يوافق رايهم

“In a narration, the credibility of the narrator is judged by his truthfulness, trustworthiness, and reliability in faith and character. Even narrators who belong to innovators (*ahl al-bidʿah*) can be deemed reliable if they are truthful, even if their narrations coincide with their own sectarian views.”

(al-Ba’ith al-Hathith Sharh Ikhtisar ʿUloom al-Hadith, p. 95)

Al-‘Allāmah Shaykh ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Yahya al-Muʿallimī al-ʿIlmī al-Yamanī explains further:

هذا وقد وثق أئمة الحديث جماعة من المبتدعة واحتجوا بأحاديثهم وأخرجوها في الصحاح، ومن تتبع رواياتهم وجد فيها كثيراً مما يوافق ظاهره بدعهم، وأهل العلم يتأولون تلك الأحاديث غير طاعنين فيها ببدعة راويها ولا في راويها بروايته لها

“Indeed, the imams of hadith authenticated and relied upon the narrations of a group of innovators (*al-mubtadiʿah*), and they included these hadiths in the Ṣiḥāḥ. Anyone examining their reports will find many that appear to align with the innovators’ doctrines, yet scholars interpret these narrations without faulting the narrator for innovation or the content for aligning with innovation.”

(Al-Tankīl bima fi Ta’neeb al-Kawtharī min al-Abāṭil, p. 238)

Abu Bakr Khateeb al-Baghdādī dedicates an entire chapter on this principle:

بَابُ مَا جَاءَ فِي الْأَخْذِ عَنْ أَهْلِ الْبَدَعِ وَالْأَهْوَاءِ وَالِاحْتِجَاجِ بِرِوَايَاتِهِمْ … وروى الخطيب بسنده الى ابن أبي حاتم قال : حدثني أبي قال : أخبرني حرملة بن يحيى قال : سمعت الشافعي يقول : لم أر أحداً من أهل الأهواء أشهد بالزور من الرافضة

“Chapter: What Has Been Related Regarding Taking from the People of Innovation and Desires and Relying on Their Narrations… Al-Khaṭīb, through Ibn Abi Ḥātim, reports that Imam al-Shāfiʿī said: ‘I have not seen anyone among the people of desires who gives false testimony except for the Rafidah.’”

(Al-Khatīb, Al-Waḍʿ fī al-Ḥayth, p. 339)