Imam Ali (as) and the Uthman Crisis: Upholding Justice Amid Grievances

Iḥsān Ilāhī Ẓahīr, in Shī‘a and Ahl al-Bayt (p. 256), criticises Shi‘a scholars for allegedly claiming that Imam Ali (as) permitted the killing of Uthman ibn ʿAffan:

“Considering this, I do not know how al-Majlisī could be so audacious to say the following while claiming to follow the Ahl al-Bayt and their Madh-hab, ‘Amīr al-Mu’minīn ʿAlī permitted his killing, and he did not see any fault in doing so.’ Considering the statement of ʿAlī, how can this be true? Over and above this, Nahj al-Balāghah is filled with the statements of his infallible Imām, which according to his claim cannot err. Statements which say that he is free from the killing of ʿUthmān and anybody involved with it. Whoever studies Nahj al-Balāghah, or even reads it, will bear testimony to this fact. But then again, who are we talking about? A nation whose hearts have been eaten by jealousy, and whose sights have been blinded by it. And whosoever Allah has not granted light to see will never find any light.”

Al-Majlisī’s statement that Amīr al-Mu’minīn ʿAlī (as) “permitted [ʿUthmān’s] killing” must be read with precision. Historical records and ʿAlī’s (as) own statements make clear that, while he recognised the legitimacy of public grievances against ʿUthmān and did not obstruct those acting on them, he neither personally participated in the killing nor encouraged anyone to commit it.

In other words, ʿAlī (as) distinguished between acknowledging the justice of popular dissent and being complicit in violent acts. He understood the public’s grievances and acted with moral and judicial prudence, yet he remained personally uninvolved in the aggression. This crucial distinction provides the necessary framework for examining his conduct in the historical record:

Reply One: Distinguishing Personal Innocence from Recognition of Grievances

Historical records, particularly Sunni sources, clarify this matter. Imam Ali (as) did not personally participate in the killing of ʿUthmān, nor did he give any explicit permission to commit it. At the same time, he recognised that the public grievances against ʿUthmān were legitimate. These two realities are not contradictory. One can maintain personal innocence and distance from culpability while simultaneously understanding or acknowledging the validity of public dissent. To illustrate logically: a teacher may not beat a student herself but may recognize that the student’s disobedience justifies disciplinary action. She neither encourages violence nor participates in it, yet she sees the outcome as appropriate. Similarly, Imam Ali (as) neither aided nor abetted ʿUthmān’s killing but understood the legitimacy of the opposition’s grievances and did not obstruct them.

Reply Two: Imam Ali (as) and the Egyptian Delegation — Integrity Amidst Sedition

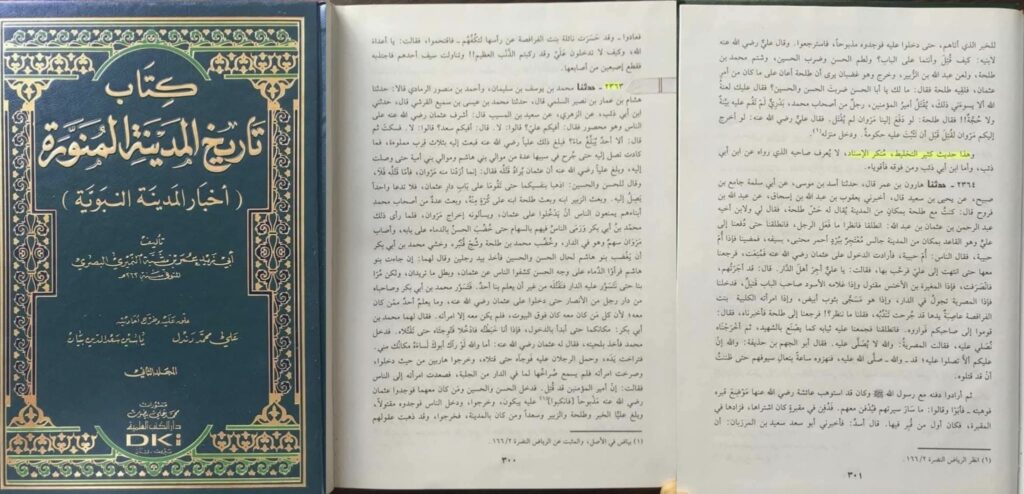

Ibn Shabbah al-Namiri (d. 262H), in Tarikh al-Madina, records that when letters arrived from Egypt reporting ʿUthmān’s harmful orders, Imam Ali (ra) responded with judicial prudence:

حَدَّثَنَا عَمْرُو بْنُ الْحُبَابِ قَالَ: حَدَّثَنَا عَبْدُ الْمَلِكِ بْنُ هَارُونَ بْنِ عَنْتَرَةَ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنْ جَدِّهِ قَالَ: لَمَّا كَانَ مِنْ أَمْرِ عُثْمَانَ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ مَا كَانَ قَدِمَ قَوْمٌ مِنْ مِصْرَ مَعَهُمْ صَحِيفَةٌ صَغِيرَةُ الطَّيِّ، فَأَتَوْا عَلِيًّا رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ فَقَالُوا: إِنَّ هَذَا الرَّجُلَ قَدْ غَيَّرَ وَبَدَّلَ، وَلَمْ يَسِرْ مَسِيرَةَ صَاحِبَيْهِ، وَكَتَبَ هَذَا الْكِتَابَ إِلَى عَامِلِهِ بِمِصْرَ : أَنْ خُذْ مَالَ فُلَانٍ وَاقْتُلْ فُلَانًا وَسَيِّرْ فُلَانًا، فَأَخَذَ عَلِيٌّ الصَّحِيفَةَ فَأَدْخَلَهَا عَلَى عُثْمَانَ فَقَالَ: أَتَعْرِفُ هَذَا الْكِتَابَ؟ فَقَالَ: «إِنِّي لَأَعْرِفُ الْخَاتَمَ» ، فَقَالَ اكْسِرْهَا فَكَسَرَهَا. فَلَمَّا قَرَأَهَا قَالَ: «لَعَنَ اللَّهُ مَنْ كَتَبَهُ وَمَنْ أَمْلَاهُ» . فَقَالَ لَهُ عَلِيٌّ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ: أَتَتَّهِمُ أَحَدًا مِنْ أَهْلِ بَيْتِكَ؟ قَالَ: «نَعَمْ» . قَالَ: مَنْ تَتَّهِمُ؟ قَالَ: «أَنْتَ أَوَّلُ مَنْ أَتَّهِمُ» ، قَالَ فَغَضِبَ عَلِيٌّ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ فَقَامَ وَقَالَ: وَاللَّهِ لَا أُعِينُكَ وَلَا أُعِينُ عَلَيْكَ حَتَّى أَلْتَقِيَ أَنَا وَأَنْتَ عِنْدَ رَبِّ الْعَالَمِينَ

Abd al-Malik, narrating from his father and grandfather, reports that when the sedition against ʿUthmān (ra) arose, a group came from Egypt carrying a small letter. They told ʿAlī (ra): “This man has altered and changed… He has written this letter to his governor in Egypt: seize wealth, kill, and exile people.” Ali (ra) presented it to ʿUthmān (ra) and asked: “Do you recognize this letter?” He replied: “Indeed, I recognize the seal.” Ali said: “Break it open,” and it was read. ʿUthmān cursed the author and the scribe. Ali asked: “Do you suspect anyone from your household?” He said: “Yes.” Ali asked: “Whom do you suspect?” He replied: “You are the first I suspect.” Ali became angry and said: “By Allah! I shall neither help you nor oppose you until we meet before the Lord of the Worlds.” (Ibn Shabbah al-Namiri, Tarikh al-Madina, pp. 1154–1155, 1167)